Tag: world aids day

World AIDS Day at the Mexican Consulate in San Francisco

For more information please contact Jorge Zepeda at 415-734-8011.

Celebrating the Latine Community at the AIDS Memorial Grove

For more information please contact Jorge Zepeda at 415-734-8011.

World AIDS Day 2023

On this World AIDS Day, San Francisco AIDS Foundation reflects on our past while looking ahead to the future of HIV. We pay tribute to the countless individuals—leaders, activists, survivors, volunteers, educators—who courageously confronted the growing epidemic in our community. We also mourn the loss of numerous loved ones, friends, and family members. Additionally, we celebrate the resilience of the survivors who have paved the path, demonstrating what it means to thrive while living with HIV. Today, we carry with us the weight of more than four decades of HIV and AIDS history, all while remaining optimistic about a future marked by health equity for all.

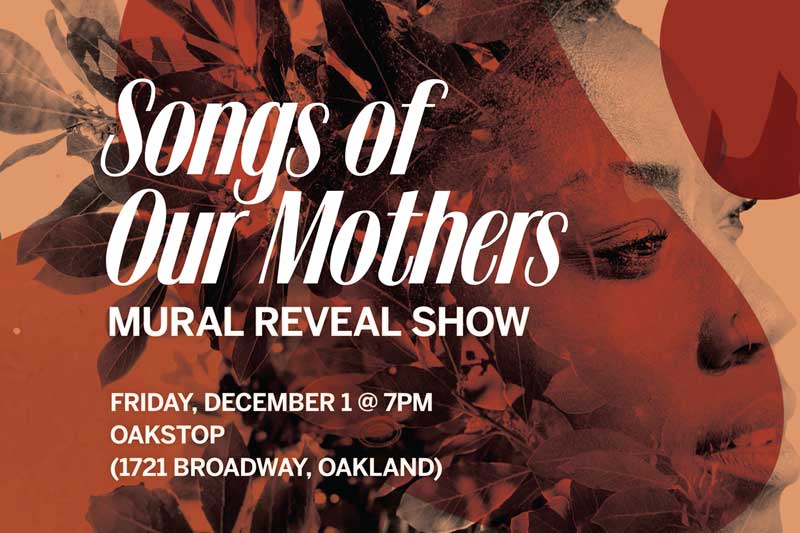

Songs of Our Mothers Mural Event

Join us on World AIDS Day as the Founding Mothers of HUES (Healing and Uniting Every Sista) come together to share their remarkable journeys as long-term survivors of HIV. Songs of Ours Mothers will be the 120th mural added to the Singing Tree Forest, bringing together visual art and storytelling to transform isolation, disconnection, alienation and violence.

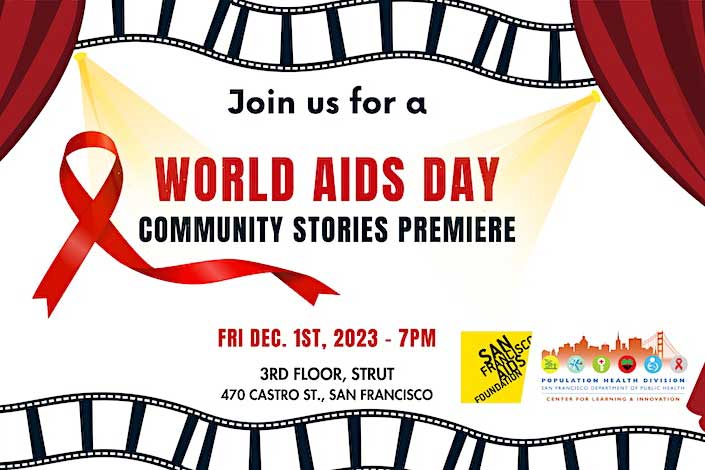

Community Stories Premiere

Immerse yourself in the power of digital storytelling. Come celebrate with us the experiences of communities most impacted by HIV/AIDS and how they’ve overcome challenges to access quality sexual health care and services. Together, let’s raise awareness, foster empathy, and honor the resilience of these communities!

World AIDS Day 2023: A Long-Term Survivor Reflects on the Past and Present

In 1987, James W. Bunn and Thomas Netter, public information officers for the Global Programme on AIDS at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, conceived of an international day dedicated to raising awareness about HIV and the AIDS pandemic. They presented their idea to Dr. Jonathan Mann, Director of the Global Programme at the United Nations (now UNAIDS), who liked and approved their recommendation. Since 1988, every Member Nation of the U.N. has recognized December 1 as World AIDS Day.

I’m not one to assign mystical significance to numerological coincidences, but… World AIDS Day was first commemorated in 1988, just one year before my own diagnosis with HIV. And WAD is now 36 years old — just as I was 36 in 1989 when I was diagnosed. And at the time of my diagnosis, I had lost 36 of my friends to AIDS.

That’s when I stopped counting. The deaths haven’t stopped, just my counting them. The grief we all experienced during and since the first fifteen years of the pandemic has been amplified by the other struggles we long-term survivors of HIV/AIDS encounter every day.

To understand what we lost in the 80s and 90s, we need to start with just a brief glance at what was happening in San Francisco and other American cities during the 1970s. For that, I’d like to quote my friend Harry Breaux, one of the five activists who co-wrote The San Francisco Principles 2020, who moved here in 1970. “At that time,” Harry says, “the skies opened up and it started truly ‘raining men.’ Lesbians and gay men attained previously unheard-of sexual and social freedoms, and the world looked hopeful for gays of all types to attain some degree of protection from harassment. We made courageous lifestyle choices that brought the homosexual genie out of the closet unlike anything that had ever happened before. Those brave men and women are basically the ones who died in the early 80s after the [HIV] incubation period ran out for so many.”

All of my adult life I had wanted to live in San Francisco to experience the freedom and the sense of liberation that this city has always stood for. I finally moved here in August 1980. In less than a year, I saw that sense of freedom and liberation turn into abject terror. During those first fifteen years from 1981 to 1996, my generation, the AIDS Generation, was literally decimated. Unless you lived through those years, it’s impossible to understand just how quickly and how brutally our friends got sick, suffered immeasurable pain, withered, and died. Friends that we were intimate with, friends whom we ran into regularly at the bars, friends that we went dancing with on weekends or invited into our homes for winter holiday meals — no one was spared. In those days, before the advent of any successful treatment, an HIV diagnosis was tantamount to a death sentence. I’ve written elsewhere that our doctors handed us the HIV diagnosis with one hand and a death certificate with the other, just waiting for the appropriate date to be filled in. If you were a gay man in San Francisco in the 1980s and early 1990s, you were terrified of contracting HIV.

But grief, fear, and death were not the only horrors we faced in those days. If we gay men were afraid of contracting HIV, the rest of the world was terrified of US. We were ignored by public health officials; we were laughed at by politicians; and we were condemned to hell by religious leaders who told us that AIDS was their god’s punishment for being queer. In Congress there was actually a proposal that all HIV+ people be TATTOOED and quarantined in concentration camps. Insurance companies cancelled the policies of HIV-positive clients and denied new coverage to anyone with HIV as a pre-existing condition. Many doctors and dentists simply refused to treat us; funeral homes refused to bury us. To say that people who were HIV-positive were treated as lepers would be a generous assessment.

Because we were treated as lepers, many of us lost our jobs to fear of the virus. Many of us were kicked out of our rental homes due to fear of the virus — I know at least four men here who lost their jobs, were illegally evicted from their apartments, and ended up living on the streets. Because they were HIV-positive. Even worse, many of us were abandoned by our families — I’ve heard horror stories about men with HIV who went home to see their families one last time, but were denied entrance into the family home, left to die alone. Other family members wouldn’t let us around their young children. And so innumerable young men died without even the comfort of home.

So the first fifteen years of the AIDS pandemic were pure hell for us, and not only because of the ravages of the disease. Things improved somewhat in 1996, when the first “cocktail” of highly active antiretroviral treatment became available and saved the lives of millions of people. But saving our lives led to other problems, what my friend the activist Matt Sharp has called “the unintended consequences of surviving.”

HIV is no longer an automatic death sentence — at least, not in this country. Many of us have lived with the virus in our blood for decades now. There are currently 1.7 million people living with the virus in the United States — and 55% of us are over the age of fifty; the CDC estimates that by 2030, that percentage will be 70%. Here in San Francisco, long-term survivors already make up some 75% of people living with HIV. All of this means that there is an entire population of HIV-positive people that has only recently been recognized as a unique cohort of patients with unique needs. The reason for this late recognition is fairly clear: Even with the most effective antiretroviral treatments, no one expected us to live this long. The very notion of “aging with HIV” was impossible to imagine when AIDS was considered a death sentence. And thus, we are now living lives that we never expected to have.

Another reason that there has been so little research into the effects of living for decades with HIV is a little more insidious. After the cocktail was introduced in 1996, the medical community pretty much turned their backs on us. Their attitude seemed to be, “Hey! We gave you the medicine, we saved your lives, now go sit in the corner and take your drugs like a good little guinea pig and leave us alone!” It is only recently, and due to the demands of us long-term survivors, that we have received any substantial attention.

From the research that has been done, we know the following —

- People over fifty who are living with HIV are subject to the same health concerns as the general population when it comes to the effects of aging. However, HIV-positive people experience those effects at an accelerated rate, sometimes twelve to fifteen years earlier than HIV-negative people. As I’ve written elsewhere, “Sixty-five is the new 80.”

- Our immune systems especially age prematurely, making us more susceptible than our HIV-negative counterparts to cardiovascular disease, heart attacks, osteoporosis, bone loss and frailty, Hepatitis C and other diseases of the liver, balance issues that lead to crippling falls, kidney malfunction, premature hearing loss, blindness due to CMV infection, diabetes, cancer and leukemia, and the one that scares me to death, dementia.

- Today, most long-term HIV survivors live below the national poverty level and need financial help for rent, food, and the cost of medications, doctor visits, and therapy. Many times when we were diagnosed in the 80s or 90s, our doctors assured us that the best thing we could do for our health was to stop working and live on Social Security Disability Insurance for the one or two years we had left to live. And so, many of us did exactly that, on doctors’ order — we quit work, went on SSDI, sold our stocks, emptied our savings accounts, maxed out our credit cards, and decided to live as best we could for the limited time left us. And then a funny thing happened — we didn’t all die! So now here we are in what was supposed to be our Golden Years, living on very small, fixed incomes in a time when the cost of everything skyrockets every day.

- The psychological impact of aging with HIV is immeasurable. Imagine spending the entire decade of your twenties or thirties… burying your friends, burying your lovers, your cousins and uncles, or even your dad. NO ONE should ever have to deal with that much death and chaos and terror even once, let alone constantly day-after-day over a fifteen-year period. We long-term survivors have lived with death as a constant in our lives for three or four decades. The psychological trauma of that lingers forever — it even has a name, AIDS Survivor Syndrome.

- Perhaps the most damaging psychological effect of aging with HIV is the isolation and loneliness it brings. When you’ve lost your entire social circle, when you’ve buried all your friends, the grief can lead to self-isolation and a disconnect from the community. That kind of loneliness and isolation often lead to alcohol and substance use, as well as cognitive decline. In some large cities like San Francisco and New York, there are AIDS service organizations like San Francisco AIDS Foundation and Shanti that work to alleviate that isolation in the HIV community, providing social events and other ways to connect with other survivors. But those ASOs can reach only so far — what about those long-term HIV survivors living in rural parts of Arkansas or Iowa or West Virginia who cannot access the help offered by those ASOs?

The challenges faced by us long-term HIV survivors are virtually hidden to all but those of us who suffer from them. World AIDS Day was conceived to honor our friends, lovers, and family who succumbed to this hideous disease. The rituals we perform on that day — such as reading the names from the Names Project AIDS Quilt and writing the names of our dead on the sidewalks on Castro Street for “Inscribe” — are important means of ensuring that we keep those whom we’ve lost in our hearts and minds. I sincerely urge that we also recognize the trauma suffered by those of us who survived AIDS and continue to live with HIV more than forty years after the beginning of the Plague Years. Spill a drop for those who are gone, shed a tear for those who remain.

In Conversation: A reflection on World AIDS Day with Dr. Tyler TerMeer, Cleve Jones, and Dr. Paul Volberding

Forty years ago, in December, 1982, fear of AIDS loomed large. Gay men went from health, to sick, to dead within days. People lost lovers, friends, partners, children to a mysterious disease with no known cure. After a diagnosis of the dreaded Kaposi’s sarcoma, the likelihood of death within two years was more than 80%. The likelihood of death within five years was all but guaranteed.

In 40 years, we’ve come a long way in our response to HIV and AIDS. We have fast, reliable tests to detect the virus that causes AIDS. We know precisely how HIV is transmitted, and we have effective medications that can prevent HIV transmission. We have powerful antiretrovirals that suppress HIV to “undetectable” levels and enable people with HIV to live long and healthy lives. We have comprehensive support and wrap-around care for people who are newly diagnosed and people living with HIV. And we have done much to end stigma and discrimination around HIV and AIDS.

This World AIDS Day, San Francisco HIV leaders reflect on this history–what we’ve lost, what we’ve gained, and what more we need to do to reach the end of HIV and AIDS. Tyler TerMeer, PhD, is the CEO of San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Cleve Jones is an author, activist, and co-founder of San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Paul Volberding, MD, is a long-time HIV physician and also co-founder of San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

Dr. Tyler TerMeer: It’s a pleasure to speak with you, Cleve, and Dr. Volberding, as always. And what an honor to lead SFAF and reflect on its long history of activism, education, and service. World AIDS Day, founded in 1988, is a day when many of us reflect on those we’ve lost to the epidemic. It’s a day when I think about my own journey living with the virus and the incredible people, like the two of you, it has brought into my life both personally and professionally.

Would you share what you’re thinking about on this World AIDS Day?

Dr. Volberding: World AIDS Day serves as a reminder that we still have a job to do. We have so many tools to end the epidemic, but huge challenges remain. Early in the epidemic, AIDS was in the news all of the time. But these days, that’s faded. World AIDS Day helps bring coverage and awareness about HIV and AIDS to the forefront, which is important.

Cleve Jones: This is true for me as well. World AIDS Day is a reminder that we can’t win these fights if we don’t have global solidarity. These are global struggles, and there are international challenges. Just as we’ve seen with Covid-19, nations don’t live separately from others. Our lives are interconnected, and our struggles against disease and poverty and racism are also interconnected.

I think it’s imperative that we raise awareness about how HIV and AIDS continue to be a major global health issue. It may feel like AIDS is a concern of the past, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. We have more than 40 million people living with the virus, and 1.5 million new infections happening every year. There are incredible challenges that just haven’t been solved.

Dr. Volberding: The discussion about equity is hugely important, and something that needs to be talked about this World AIDS Day. San Francisco has made a lot of progress, but we must reflect on how there are so many communities in our country, and of course around the world, that are not similarly benefiting. We must renew our focus on that.

Dr. TerMeer: That’s an interesting point, Dr. Volberding. San Francisco has made a lot of progress, and in many ways is seen as a leader in HIV and AIDS innovation, prevention, and care. That of course is due to the groundbreaking work that you both–and many other leaders in HIV and AIDS in the Bay Area–did in the early years of the epidemic. You identified the needs of the community, and acted quickly to call attention and resources to the issue. What can you share with us about that moment in history, and the moments that led to the founding of San Francisco AIDS Foundation?

Dr. Volberding: This was a time when there was so little reason for hope. I do remember sitting at the table with Marcus Conant and others who were leading the effort. It was a very humble start–a very grassroots effort. People involved in the AIDS response were willing to stand up, and do the work, at a time when so many people weren’t. From those beginnings–and now, to reflect on the work that the foundation has done, bringing the community together and focusing on advocacy, that is something to celebrate.

Cleve Jones: I agree that there felt like little reason for hope in those early years. Many of us were terrified, and many of us were angry. We knew–and we were right–that Washington wouldn’t respond in the ways that were needed to this new threat. If we wanted to save our community, we’d have to step up and do it ourselves.

Dr. TerMeer: You all certainly did step up. Hearing about that time–the marches, the vigils, the acts of civil disobedience, and the services that were built–it’s as inspiring as it is heartbreaking. Since this is World AIDS Day, what can you tell us about the very first World AIDS Day in San Francisco?

Cleve Jones: The history of World AIDS Day has a connection to San Francisco, through the incredible reporter named Jim Bunn. In the early 1980s, Jim worked with KPIX, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, and the Department of Public Health to create news stories that shared solid information about AIDS, and the real-life stories of people affected by AIDS and its resulting stigma and discrimination. Because of his reporting on AIDS, Jim went on to work at the World Health Organization. He and a colleague, Tom Netter, proposed a “day” to focus media and community attention on HIV and AIDS. The idea was pushed forward by Dr. Jonathan Mann, an extraordinary hero in the early fight against AIDS.

I met Dr. Mann that year at the International AIDS Conference in Stockholm. He was very moved by the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which we had begun just one year before in 1987. He reached out to my team at the Quilt, and had this idea to bring the Quilt to New York City at the United Nations headquarters, Geneva at the World Health Organization headquarters, and Bangkok, London, Sydney, and Brazil. People ended up bringing sections of the Quilt in their backpacks to these locations across the globe. It was the first visual symbol of international solidarity in AIDS.

Dr. TerMeer: It sounds incredibly powerful and I’m sure that it was also incredibly meaningful to so many being impacted by AIDS. Thank you both for sharing your memories, and for all you continue to do to raise awareness about HIV and AIDS. As you’ve said, our work is not done. Today is a day for us all to reflect and remember that.

Cleve Jones is co-founder of San Francisco AIDS Foundation, creator of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, and author of When We Rise: My Life in the Movement. He is a human rights activist with a history of activism spanning five decades.

Tyler TerMeer, PhD, is CEO of San Francisco AIDS Foundation and co-chair of the AIDS United Public Policy Council. He is passionate about improving the health of people living with HIV, ensuring that LGBTQ+ people have access to affirming care, and supporting and empowering Black-led organizations and BIPOC leaders. Dr. TerMeer has been honored by the White House as one of the “Nation’s Emerging LGBTQ+ Leaders,” and as part of the “Nation’s Emerging Black Leadership.”

Paul Volberding, MD, is a cancer specialist who has spent his career responding to the HIV epidemic. He is a cofounder of San Francisco AIDS Foundation, founded the first inpatient ward for people with HIV and AIDS at San Francisco General Hospital, and worked in clinical trials to develop antiretroviral therapies. He has previously served as the co-director of the UCSF-Gladstone Center for AIDS Research, as the Chief of the Medical Services at the San Francisco VA Medical Center, the Director of the UCSF AIDS Research Institute, and the Director of the amfAR Institute for HIV Cure. He is the Clinical Editor in Chief of the Journal of the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes.

World AIDS Day 2022

This year on World AIDS Day, San Francisco AIDS Foundation remembers our history as we look to the future of HIV.

We honor the many leaders, activists, survivors, volunteers, and educators who took bold steps to confront an epidemic growing in our community. We mourn the loss of so many of our lovers, friends, and family members, and we celebrate the many survivors who have paved the way and defined what it means to live well with HIV. On this day, we hold the difficult memories from 40 years of HIV and AIDS, and at the same time look forward to a future of health justice for all.

Join us for a World AIDS Day 2022 event.

Get involved

World AIDS Day is a Day to Heal our Grief

World AIDS Day. For most, it is a global event where we honor, memorialize, and celebrate the lives of those we have lost to HIV and AIDS since the pandemic began in 1981. For me it is so much more.

During those early years of the AIDS pandemic, many of us long-term survivors experienced nothing short of a catastrophic loss of life–losing friend, after lover, after friend, after lover, after friend within a very short period of time. At the height of the AIDS pandemic, there were many of us who were attending an average of four memorials a week, in some cases, six or more.

Psychologists call what we experienced “compounded grief,” something that can occur during and after a mass casualty event such as war or natural disaster. Entire communities were affected, and like other events that result in mass casualties, collective grief manifested. We felt powerless to control the crisis consuming us.

Years later, we feel anticipatory grief. We are scarred by our pasts, seeing the loss around us and the problems not yet fixed as we confront new pandemics (Covid-19, MPX) and crises.

What can we do to heal?

I’ve found comfort in these four steps, and I make sure to incorporate them into every day of commemoration, including World AIDS Day. They are: Acknowledge, Memorialize, Take a Break, and Take Action.

Last year, on December 1, 2022, I took a break from my daily life to focus on the grief that I normally tend to push down. This is normally an act of self-preservation: I push my grief away so that I can function. Most days, if I dwell on my grief, it would overwhelm and consume my very soul. On World AIDS Day, I let my emotions surface.

The day began with Inscribe. Created by George Kelly, in 2016, Inscribe began as a way to teach the students at the Harvey Milk Civil Rights Academy about those early days of the AIDS pandemic. As a community–students, parents, teachers, neighbors, merchants, tourists, and community leaders–we inscribe the names of those we have lost along two full blocks of Castro Street sidewalks using chalk. By the end of the day, the sidewalks along Castro Street are a patchwork of chalk art, reminiscent of The AIDS Memorial Quilt. It is a powerful act of acknowledgement and a way to memorialize those we have lost.

The display–and the collective act of remembrance–brought tears to my eyes.

Later that day, closer to sunset, we held a Vigil1 on the steps of San Francisco City Hall, where we acknowledged the contributions of civic leaders and others, past and present who were essential in the creation the service and safety network that San Francisco sets as the standard of care for those living with and at risk for HIV.

Then we marched. Just like we did those early days we held candles in one hand and protest signs in the other. Reminding people that HIV and AIDS is not over.

By marching from the steps of City Hall to the steps of St. John the Evangelist Church, we reminded people that there are still 16,000 people in San Francisco living with HIV and that over seventy percent of them are over the age of fifty. We were led by Ms. Billie Cooper, who reminded us that even forty years later, there are still disparities among communities including among trans and Black and brown communities. Dr. Monica Gandhi, from Ward 86, called upon us to refocus our efforts on ending the HIV epidemic, marched with us. And afterward…

…we DANCED!

Under a sky of Quilt panels hanging from the ceiling of the church–made up of panels of parishioners lost to AIDS–we celebrated and memorialized all who were lost.

We danced to the music made popular by the Sunday Tea Dances popular in the early years of AIDS. I danced to honor Jerry, my first friend who died. I danced to honor Vincent, the love of my life who I had buried, not even three months earlier on October 14, 2021, a day before his forty-sixth birthday. I danced to honor those who stuck by us and cared for us over the years. I danced to honor those who lost not one, not two, but three partners and yet still continued to fight alongside us. I danced to honor those young people who continue to fight on my behalf so that I may continue to have access to the services that I need.

I laughed. I cried. And I was healed just a little bit more than I had been a day before.

And that’s the thing. Each World AIDS Day, when I am able to join my friends, my colleagues, my peers and so many others of my community and take a break, acknowledge my loss, memorialize those losses and take action by marching or by dancing, I am healed a little bit more.

–

1This event was thanks to the combined efforts of Ande Stone and the other members from the HIV Advocacy Network, Gregg Cassin from the Honoring Our Experience group at Shanti, John Cunningham, Joanie Juster and Michael Bongiorni from the AIDS Memorial & Quilt, the folx at Black Brothers Esteem and TransLife with the help from some good friends at City Hall and the Reverend Kevin Deal and the parishioners at the Episcopal Church of St. John the Evangelist, and Dr. Monica Gandhi, from Ward 86.

Getting the Word Out

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

Our experience with COVID-19 over the last two years has reminded us that when pandemics arise, they invariably come accompanied by confusion, fear, panic, blaming, and a plethora of misinformation regarding the pandemic’s origins, treatment, and prevention. No attempt at blame (the “Chinese virus”) is too outlandish; no supposed treatment too illogical or dangerous (horse de-wormer and bleach); no claim too outrageous or impossible (microchips in the vaccines). It seems there’s nothing quite like a worldwide health crisis to bring out all the conspiracy-spouting haters.

Those of us who lived through the earlier (and still ongoing) HIV/AIDS pandemic knew to expect this reaction because we had lived through the same kinds of things nearly forty years earlier. For the first couple of years of our first pandemic, when information was scarce and often contradictory, there was quite a lot of fear, not all of it irrational — gay men were terrified of catching or spreading the disease, and straight people were terrified of us. There was no lack of panic either, as evidenced by threats to quarantine everyone with HIV in a camp and tattoo us with a plus sign on our buttocks (we can thank William F. Buckley for that charming “solution”). As with COVID-19, misinformation about HIV was rampant: “you can get AIDS from a toilet seat”; “all gay men carry AIDS”; “only gay men get AIDS.” And Ivermectin has nothing on some of the ludicrous, harmful “cures” that were made up to fleece the desperate and dying.

Getting the word out — compiling scientifically accurate, nonjudgmental information about HIV; how it is transmitted, from whom and to whom; how it is not transmitted; how transmissions can be prevented; and how it can be treated, and getting that information into the hands of people living with or at risk of acquiring the virus — became one tool in combatting the misinformation and stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS. With the advent of the Internet, disseminating information became really easy — with just a few keystrokes, one can reach untold thousands of people with a single Tweet or posting on Facebook or Instagram. But in the early, pre-Internet years of the pandemic, we relied on the technology that was available at the time: the telephone and the printing press.

San Francisco AIDS Foundation was founded in 1982 as the Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research and Education Foundation by Dr. Marcus Conant, Frank Jacobson, Cleve Jones, Richard Keller, Bob Ross, and Dr. Paul Volberding, who took quick and decisive action in response to the mysterious disease that would later be known as AIDS. In a one-room storefront on Castro Street, the agency’s first service was a telephone information and referral hotline. The AIDS Hotline started as a single-telephone volunteer-run information and referral hotline. As the pandemic spread like wildfire through the community, and as the need for concrete information grew, the AIDS Hotline grew into a full-time operation with volunteers sitting around a room full of phones taking calls.

One of those volunteers, Cal Callahan, joined the SFAF AIDS Hotline in 1984. After two weekends of training and shadowing an experienced volunteer, Cal put in at least one four-hour shift each week. He recalls that the questions he got asked most “shifted over the years. For the first few years, there was still uncertainty about transmission and most questions were about risk and symptoms. HIV testing came out in 1985 and many questions shifted to that and soon after to the treatments that were coming out. As more services came into being, many of the calls were referrals to those services. There was always a percentage of ‘worried well’ who had no risk factors but were still concerned about contracting HIV. Some of them became repeat callers.”

Volunteers were supported by the Education Department at SFAF, which sifted through the available information (“which changed often as science developed a better understanding,” Cal said). Cal’s partner Glynn Parmley developed an “encyclopedia” for volunteers to utilize, with newest information put at the front of the encyclopedia and reviewed at the beginning of each shift and in periodic update meetings. Volunteers also had access to SFAF-produced pamphlets, brochures, and fact sheets to mail to callers upon request.

Gay men were not the only callers to the Hotline. Straight folks called too, but “not nearly at the same frequency but many of those questions were about casual contact or from ‘worried well’ people. There was a subset of straight guys who wanted to know if a woman ‘might have given him AIDS’ (there was rarely a concern that he infected her). They were our least favorite callers.”

Cal has been involved with the HIV community every since.

On the opposite side of the country, in New York City, young actor, singer, and playwright Bruce Ward was just beginning his theatre career in the Fall of 1984. Through the medical editor at the New York Native, a prominent LGBTQ publication, Bruce landed an interview with the NYC Department of Health AIDS Hotline as a hotline counselor. “I thought of it as just a part-time gig, to make money, but I come from a family of counselors and teachers, and I quickly found my passion for telephone counseling,” he told me. After a brief training, Bruce began working the hotline for two four-hour shifts; after the death of Rock Hudson, his time on the hotline increased to three four-hour shifts, sometimes more. Things were relatively primitive in the hotline’s office; there were no computers in the office, so all information was recorded on mimeographed sheets of paper, and the phones were all land lines.

As with Cal at SFAF, most of the calls Bruce fielded were from people dubbed “the worried well,” “mostly heterosexual calls, about mosquitoes, swimming pools, dried blood in presumably homosexual men’s apartments. Many calls conveyed a hidden anxiety: men calling about getting the virus from women, and during the course of the call, I would find out that the man was secretly visiting [sex workers]. Also men who were closeted and married to women. But every once in a while we would get a staggeringly emotional call, from a mother, or a gay man who is afraid he had it, or a partner.”

In 1986, Bruce became Assistant Director, then Director of the CDC’s National AIDS Hotline, where he led the training sessions for new counselors. “I was overwhelmed,” he said. “I was just a hapless actor/playwright, suddenly thrust into this major political position. And when Reagan said the word, ‘America responds to AIDS’ started, and we were major players.” The CDC and the American Social Health Association, which ran the national hotline in New York City, moved the hotline’s operations to Raleigh Durham, North Carolina. Bruce was charged with training the people who would replace him and his entire staff.

“My time at the NYCDOH hotline was exhilarating. I felt as if I was at the center of something huge. And I also felt I had found a new calling, and a passion for counseling and teaching. We all felt at the time that if we just worked hard enough, we would defeat this virus… It was also exhilarating starting as assistant Director at the National AIDS Hotline. I helped the interim directors search for a space, and I loved the concept of building something from scratch. I was in charge of hiring the operators and the volunteers who worked on the hotline and, like at the NYCDOH, it felt like we were on the precipice of something huge.”

It was also at this time that Bruce tested positive for HIV. The combination of his worsening health and “the anxieties and tensions and political fumblings of the job,” and the anxiety of hiding his serostatus from his co-workers at the CDC and ASHA, Bruce hit his breaking point. “I was way over my head, and I was sick and exhausted. It was the only time I thought about taking my own life. But that job taught me something. I love teaching, and I love counseling. But I am not a policy person, or a political wonk. And that was a big lesson — I had my limits.”

Often, volunteers like Bruce and Cal report that their work affected them as much as the clients for whom they volunteered. Cal Callahan expressed it well:

“It was very affecting; I was living with HIV all around me, but this gave me the sense that I was helping other people. I had some long calls that were more about sexuality and orientation where I really felt I’d made a difference in that person’s life. People were often much more willing to share parts of their lives with an empathetic but disembodied voice than with someone who knew them.

“I learned that everyone, whether you liked them or not, deserved to be given good and useful information, and to be treated with respect. I also learned that people tend to be at their best when doing something good for others. We became a very tight-knit group for quite a while.”

In addition to the AIDS Hotline, San Francisco AIDS Foundation began publishing BETA: Bulletin of Experimental Treatments for AIDS in 1988. The Foundation had prepared and disseminated numerous brochures, pamphlets, and posters around San Francisco and beyond as part of their efforts to educate the public about HIV/AIDS. But BETA was its first magazine-length publication. Issued quarterly, BETA reviewed available scientific data on AIDS treatments as well as anecdotal information provided by physicians, researchers, people with AIDS or AIDS-related conditions, and individuals living with HIV. The magazine was distributed to clinics and AIDS Service Organizations in San Francisco as well as all fifty states and Puerto Rico. BETA was also available through individual subscriptions (free to HIV-positive low-income people living outside San Francisco). Each issue nearly burst at the seams with reliable, comprehensive, science-based, up-to-date information about the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Reports on new treatments, reviews of important drug studies, listings of then-current open clinical trials of new medications, reports on the information presented at HIV/AIDS conferences — BETA provided this and other much needed, hard-to-find information.

With the advent of HAART, articles in BETA began to offer more personally useful information, such as how to talk to your physician about your HIV status, the effects and side effects of new medications, the possibility of multi-drug interactions, food safety guidelines, combatting HIV drug-related diarrhea, and other real-life issues. BETA was also one of the first publications to address the issues specific to women with HIV, including mother-to-child transmission of the virus and gender-related differences in responses to antiretroviral therapy. In 1997 and 1998, the magazine also produced and distributed a series of “Information Sheets” on the protease inhibitor drugs and treatment strategies.

In 1992, John Maguire introduced the comprehensive computerized database as a joint effort of SFAF and the SF Public Library (John worked for both). That began the shift to online information. BETA first went online in 1994; the website highlighted the then-current issue and made past issues of BETA available for download as PDF files. In 2013, on the publication’s twenty-fifth anniversary, BETA Blog became an online-only publication with a new mission statement: “BETA reports on developments in HIV prevention, treatment, and strategies for living well with the virus. BETA promotes health literacy and provides tools to help readers understand meaningful developments in HIV research, access medical treatment, and get the greatest benefit from care.”

From its inception, San Francisco AIDS Foundation has prioritized getting the word out about HIV/AIDS, how the virus is transmitted, how to prevent transmissions, available treatments, how to access healthcare services, how to access other services and benefits, how to get and use PrEP, and other issues around the virus like systemic racism, homophobia and transphobia, misogyny, and navigating the for-profit healthcare system. After you’ve finished reading this article, browse through the rest of the Foundation’s website. You’ll find articles about advocacy for trans individuals, racial equity in healthcare, anal health and sexual health, the FDA approval of a condom for anal sex, and much, much more. Forty years into the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the Foundation can still be relied upon for current, accurate, science-based, useful information. Please put it to good use!

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.

We must re-focus our attention on HIV and AIDS

World AIDS Day, held December 1 every year, is an opportunity for people living with HIV and other people who have been touched by the epidemic to come together in remembrance of those we have lost–and to keep the spotlight focused on everything we still must do to end the HIV epidemic once and for all. Amidst the pain and suffering caused by the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, a worsening overdose crisis, poverty, housing shortages and more–all of which disproportionately affect people living with and at risk for HIV–World AIDS Day should have been even more revered as a time for San Franciscans to come together on this special day.

But, last month on World AIDS Day, things felt different. Most of the world’s attention was diverted to the newly surging Omicron variant of the Coronavirus that causes COVID-19. And although various AIDS organizations, activists, and individuals commemorated the forty-year history of HIV/AIDS on World AIDS Day, I did not see even one mention of World AIDS Day in any non-LGBTQ media. The COVID-19 has captured our collective attention and worry, but at what cost to people living with and at risk for HIV?

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a lot of setbacks in the city’s HIV response,” said Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, the Medical Director of “Ward 86,” the HIV Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital, and one of the city’s leading experts and voices on COVID-19.

HIV testing was down by 44% at community testing sites in 2020 from 2019, according to the San Francisco Epidemiology Surveillance report, said Dr. Gandhi. This is critical, because HIV testing is one of the most important strategies for identifying people with HIV early for treatment in order to prevent HIV transmission.

Dr. Gandhi also noted that rates of viral suppression (being “undetectable”), dropped in the city overall from 75% to 70% from 2019 to 2020. Among people with HIV who are experiencing homelessness, only 20% were virally suppressed (a staggering decrease from 50% since 2019). And, overdose deaths have soared in the city during this time, which has disproportionately affected the HIV community.

“I think the COVID response in the city did deflect resources and interest in combating HIV/AIDS, but I also think that HIV has been losing attention for some time. We need to refocus our efforts on the care and treatment of people with HIV and on prevention of HIV in San Francisco,” said Dr. Gandhi.

A great deal of the money and energy that might have gone into HIV/AIDS research for a vaccine or a cure were devoted to finding a vaccine and treatments for COVID-19; many scientists and researchers were pulled from their HIV/AIDS work to work on COVID. During periods of lockdowns and social distancing, trips to clinics decreased, interrupting testing and early treatment of HIV. Besides, in the scientific/medical community, there was the excitement of a “new” virus to conquer — at forty years, HIV/AIDS may feel to some like “old news.”

It will take a concerted, multifaceted, cooperative effort to bring HIV/AIDS back to the forefront in San Francisco, the U.S., and the world.

Dr. Gandhi again: “I think the HIV treating community, i.e. healthcare workers, need to team up with activists, community, and patients like we did in the 80’s to again raise awareness that HIV is not over and that more resources and support should go towards HIV/AIDS. Our strength in HIV activism has always been researchers, clinicians, patients, advocates and activists working together. We need to do this again to ‘take back’ HIV as a major priority in our city.”

HIV testing, research into vaccines and a cure, prevention activities such as the use of PrEP, treatment opportunities, and social services for those of us living with HIV or AIDS have all taken a back seat to concerns about the coronavirus and its variants these past two years, and this has been reflected in the media’s pivot from HIV and AIDS coverage.

At a World AIDS Day Rally held on the steps of City Hall, Dr. Gandhi, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, along with representatives from the HIV Advocacy Network, Black Brothers Esteem, TransLife, the HIV Caucus of the Harvey Milk LGBTQ Democratic Club, The San Francisco Principles 2020, and other local activists and advocates spoke about the importance of addressing HIV and AIDS in San Francisco and the Bay Area. Glaringly absent were members of the press, and all but a few elected officials.

“It was the 40th anniversary of the first description of AIDS on World AIDS Day 2021 and so, as Medical Director of the Ward 86 HIV Clinic, I was hoping the press coverage that day in the city would center on this important event,” Dr. Gandhi told me.

“Since San Francisco was the epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the 1980’s, it was a momentous occasion to be at the 40th anniversary of the first description of AIDS. However, that day happened to be the day the Omicron variant was first described in the US (in San Francisco) so the news coverage that day was almost exclusively on this variant. We had a rally on the front steps of City Hall, but there was no press there, nor presence from city officials. I was sad that this day went by relatively without the city of San Francisco commemorating it in a huge way given the importance of HIV/AIDS to our city’s history.”

As an infectious disease expert, Dr. Gandhi was called by various news agencies to comment on Omicron. “Not one of them asked me about World AIDS Day. I was very disappointed,” she said.

As we begin a new year, let us not lose sight of HIV and AIDS–everything that still must be done, but also the incredible progress we have already made.

World AIDS Day 2021

December 1 is World AIDS Day, a day for us to commemorate those we’ve lost, those living with HIV, and all those who work to ensure Health Justice for All. This year, we mark 40 years in the movement to end the HIV epidemic.

World AIDS Day Candlelight Vigil and March

Join us this year for World AIDS Day on the steps of San Francisco city hall to remember those we’ve lost to the HIV/AIDS crisis and to issue a call to action for justice for our communities. Candles will be provided. Meet at 4 pm in front of San Francisco’s City Hall on December 1.

Health Justice for All Tarot Designs

This World AIDS Day, we express our passion for a more balanced, equitable, and just world through the art and practice of Tarot. With three cards, we share our vision of Health Justice for All.

AIDS/LifeCycle World AIDS Day Broadcast

Join the AIDS/LifeCycle community for a very special World AIDS Day Broadcast, on December 1st at 6 pm PT. Tune in for special performances, shared community stories, and a live candlelight vigil led by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

Latinx Health Event in National AIDS Memorial Grove

Our Latinx Health team with El Grupo will host an event at the National AIDS Memorial Grove boulder commemorating the Latinx communities affected by HIV and AIDS, with a gratitude to Mother Earth, mariachis, an art installation, and a meal. Join us in the National AIDS Memorial Grove on December 3, 12 pm – 3 pm.

Showing posts 1 – 17 of 17