The Long View on Harm Reduction in San Francisco

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

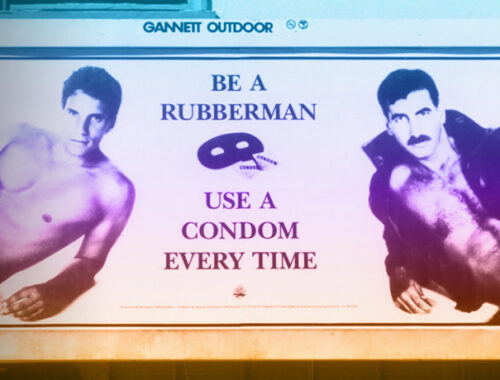

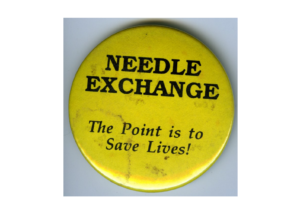

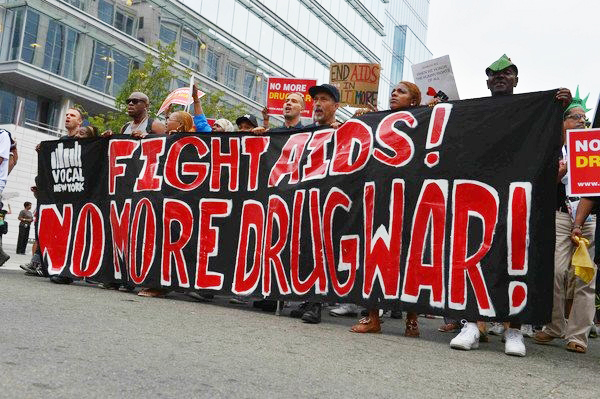

San Francisco is known for being a leader in harm reduction–one of the first cities in the U.S. to build up a successful needle exchange program in the ‘80s and ‘90s, that now includes a comprehensive network of compassionate services for people who use drugs. San Francisco AIDS Foundation was part of that historic time, and continues to be on the forefront of the harm reduction movement to this day, with staff that are intensely devoted to the rights, health, dignity, and care of people who use drugs.

Two of our leaders at SFAF, both with long histories in the harm reduction movement in the Bay Area, shared with us some memories from the early years of their work. And, they offer us the long view on harm reduction in the Bay Area–how has it progressed? And, where is it going?

“Sometimes nothing feels different than when I first started doing harm reduction work,” said Ro Giuliano, our director of Syringe Access Services and PWUD (people who use drugs) Health. “Sometimes everything does. It does feel like we’re on the edge of something… I do think we’re on the precipice of doing some really innovative things.”

Giuliano, who began working in harm reduction in the mid-90s, pointed to one aspect of her work that has changed a lot in the last 20 years: overdose prevention and response.

“I was showing a colleague recently an old overdose prevention handout that was sharing tips on rescue breathing and sternum rubs,” said Giuliano. “We go from that to now–when we’re able to provide naloxone to people to prevent overdose. We were able to give out 40,000 doses last year. Realizing that we’re able to do this type of work now, it’s a lot.”

Naloxone, available in medical settings to healthcare practitioners since the early 1970s, has only in more recent years been legal to distribute freely to people who use drugs and their communities. Activists and people who used drugs realized that overdose deaths could be avoided, and that people who used drugs should be empowered to actively prevent fatal overdose with the proper resources and training.

One of those activists, shared Giuliano, was Dan Bigg, who would visit San Francisco and other cities with duffle bags full of Narcan, distributing the medication at needle exchanges and to people who used drugs. At the time, Giuliano was operating the San Francisco Needle Exchange (SFNE), and worked with young people who used drugs in the Haight/Ashbury neighborhood near Golden Gate Park.

“It was a typical Dan Bigg story,” said Giuliano. “He would sit with a bunch of us on the top floor of 409 Clayton [SFNE’s headquarters] and teach us how to do Narcan. We were the first to push doing underground naloxone, but it took years for the city to catch up.”

“At the time, it just wasn’t that easy to get large supplies of naloxone,” said Laura Thomas, our director of harm reduction policy. “Dan’s eternal brilliance was figuring out how to get access and then re-distributing them throughout the country. So he would just travel everywhere with these duffle bags, leaving people with lots of Narcan everywhere he went.”

Current-day harm reduction work is intensely focused on overdose prevention and response, especially as the city sees rising rates of fatal overdose happening year after year. But Giuliano stressed that overdose has always been a focus of the community, although in recent years it feels “a little more amped up.”

“For people living it in the ‘90s, overdose was absolutely always a focus because people were dying around us. That hasn’t changed,” she said.

Overdose prevention policy work is currently where Thomas’ work is focused–particularly on pushing for policy change that will allow safe consumption services to open and operate legally in San Francisco. It’s an issue she’s been pushing forward for nearly 15 years.

“Every year I’m overly optimistic that this year will be the year,” said Thomas. “We’re so close, yet still so far away. But we will make it happen. There are too many lives on the line for us not to get there.”

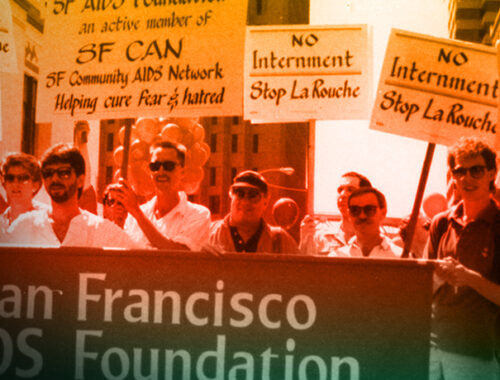

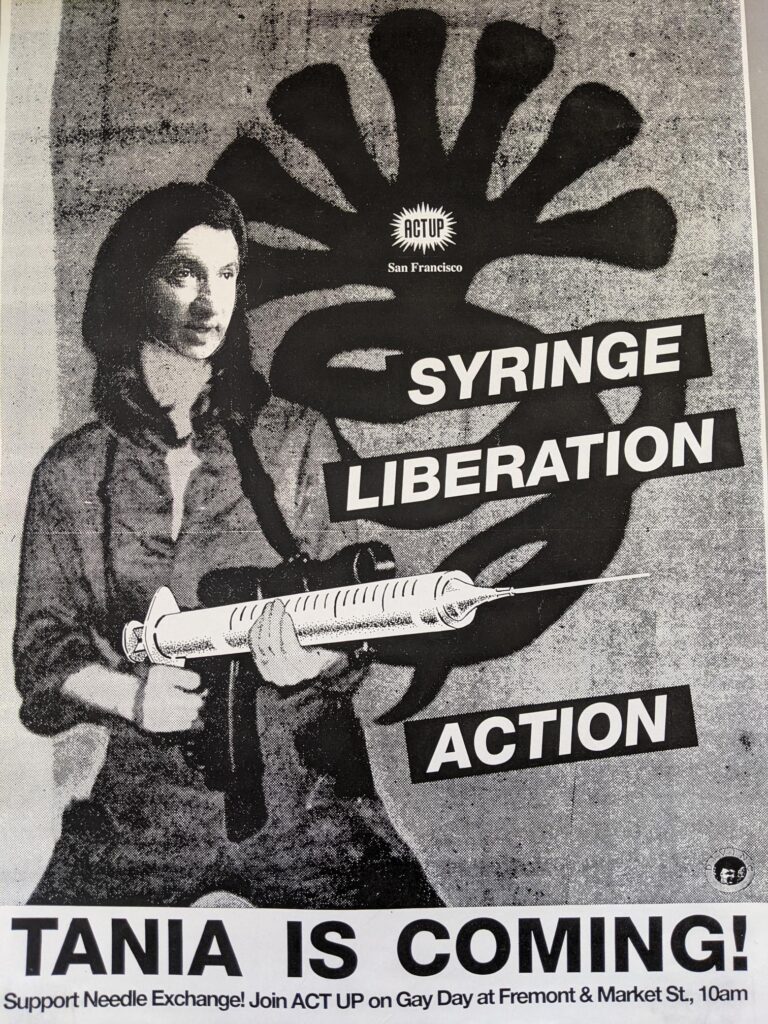

Thomas came into harm reduction work early on in the HIV epidemic through her work with ACT-UP, which she joined in 1988–the year the underground needle exchange Prevention Point was founded.

“I remember one of the first things the founding members of Prevention Point did was pass a hat to raise money at an ACT-UP meeting,” said Thomas. “I had friends who were part of Prevention Point, and ACT-UP pushed forward the advocacy around legalizing needle exchange in San Francisco.”

Thomas remembers helping to organize grassroots fundraisers and community mobilization opportunities in the late 1990s to support Prevention Point, with the gay community coming together at Pride to advocate for HIV prevention among people injecting drugs. She also took part in meetings and direct actions with the mayors of San Francisco–Art Agnos (who served from 1988 to 1992), and Frank Jordan (who served from 1992 to 1996).

“We initially targeted Agnos over legalizing needle exchange,” said Thomas, who participated in sit-ins and demonstrations at the Mayor’s office. She still owns a cut-and-paste poster from that era–a play on the Symbionese Liberation Army showing Agnos’ face superimposed on a photo of Patty Hearst with the words “Syringe Liberation Action” below.

“There was a lot of pressure on the Mayor at the time,” said Thomas. Her first meeting at City Hall with Mayor Jordan included members of Prevention Point, ACT-UP, and the director of public health who spoke about the importance of legalizing and funding needle exchange programs in San Francisco.

“I was just the punk kid with my Doc Martens and my leather jacket,” remembered Thomas. “Now I don’t bat an eye if I’m meeting with the Mayor and director of public health, but at the time I was like ‘holy crap.’ During the meeting, though, the Mayor kept getting the words for Prevention Point confused–he kept referring to the organization as ‘Needle Point.’ So the first time he said it, I looked up and caught the director of public health, Ray Baxter’s eye–we’re both trying not to burst into giggles.”

In 1993, Mayor Jordan declared a city-wide state of emergency to allow needle exchange through a newly-created organization through San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Funding flowed to Prevention Point (now re-named HIV Prevention Project, or HPP), and the work expanded with new staff and resources. Although much of the work was lauded by activists and community members, some decisions and actions proved controversial.

“I remember very much pushing back at the AIDS Foundation as a young person,” said Giuliano. “They didn’t do syringe exchange with anyone under 18. They wouldn’t do anything outside of one-for-one exchange. When Willie Brown wanted to gentrify the hell out of the Haight, and put up a fence around Golden Gate Park, San Francisco AIDS Foundation pulled their needle exchange out of that neighborhood.”

That decision led Giuliano to co-found the San Francisco Needle Exchange serving young people in the Haight. SFNE provided syringe access services three days per week, at sites which are still operated to this day by the non-profit Homeless Youth Alliance (HYA).

“This was my community, and we needed those services,” she said.

Over the years, the pushback on one-for-one exchange increased, eventually leading to less restrictive policies.

“I’m really glad that policy [of one-for-one exchanges] has gone into the dust bin of history,” said Thomas. “It created all of this tension in the moment.”

Thomas, who volunteered at the Duboce syringe access site through San Francisco AIDS Foundation for many years, said the one-for-one exchange policy put her in the position, as a volunteer, of having to enforce a policy “she knew wasn’t right.” (Research shows that open access to syringes is best for the health of people who inject.) “It made me into the person who was having to police people around the numbers of syringes they were bringing in–and only giving them the exact number that they had brought in.”

Giuliano also volunteered at a needle exchange site for San Francisco AIDS Foundation before starting SFNE. “I volunteered for a brief period of time. We didn’t do one-for-one needle exchange. And at some point we got a letter saying basically, ‘You’re no longer welcome to be volunteers at SFAF.’”

Working in the Haight in the ‘90s and into the 2000s “was just a really interesting time,” said Giuliano. “San Francisco was changing, gentrification was just rolling into the Haight. I was just a young person who was doing tons of drugs, and I was in a band, and this was my community. So I was just meeting the need that was happening. There were so many young people living in the park, and also folks who had housing in upper and lower Haight who were shooting speed and heroin. It was also this new moment in HIV work, too, because we were just starting to get good HIV meds. The tide was turning.”

Giuliano said one of the biggest changes–that she never thought she’d experience–has been seeing and responding to a new drug come on the scene.

“Supply is shifting to synthetics, whether it’s fentanyl or these novel benzos,” she said. “I never thought I’d see that in my lifetime, when tar heroin didn’t dominate in the opioid world. So to see that, and then have to shift programs and services in response–that’s been a challenge.”

Thomas said it’s actually helpful for her to look back on policy wins that have happened over the years when the current situation in San Francisco feels discouraging. She describes it as a “slow liberation”–chipping away at harmful policies that get us closer to comprehensive, compassionate, and evidence-driven care for people who use drugs.

Over the years, Thomas has seen (and been part of) changes like the decriminalization of syringe possession, pharmacy access to syringes, naloxone distribution, and pharmacy access to naloxone. One of the changes she is most proud of has been the increase in California state funding for syringe access. And now, she says, it is encouraging that the Biden administration has been supportive of harm reduction.

“The support for harm reduction has been really clear,” said Thomas. “I would like for them to follow through on their support for things like supervised consumption services. But just saying that there is support–really clear support–is a big policy change.”

Both Giuliano and Thomas acknowledge the incredible efforts of so many people who use and have used drugs who have shaped San Francisco’s response to HIV and the overdose.

“The policy wins have all come at the hand of people who use drugs,” said Thomas.

“We have lost so many people to overdose. So many of these key players, who have done the bulk of the work around naloxone. So we’re standing on all of their backs, as we continue to do this work,” said Giuliano.

Ro Giuliano is our director of Syringe Access Services and PWUD (People Who Use Drugs) Health. She leads our Syringe Access Services team, the Syringe Pick Up Crew, our overdose prevention and response services, and the services at our Harm Reduction Center on 6th Street.

Laura Thomas is our director of harm reduction policy, working to change local and state policies in order to provide resources, healthcare, overdose prevention, and services to people who use drugs. Among other issues, she is working to pave the way to establish safe consumption services in San Francisco.

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.