From caffeine, to alcohol, to stimulants and beyond, we realize that drugs are a part of our world, our culture, and at San Francisco AIDS Foundation–our workplace, through our harm reduction programming, sexual health services, policy/advocacy/community education work, and substance use counseling services. But what about for employees at work–many of us who choose to use substances? How can an organization acknowledge, and support, employees with the same harm reduction principles it shares with clients and participants?

This was an issue tackled by Kenji Aoki, a senior at Harvard University, during a fellowship with SFAF this summer. With our Employee Engagement team, Aoki researched and recommended harm reduction principles for SFAF to incorporate in our employee handbook. He’s also currently working on establishing a harm reduction-focused employee resource group for employees, and creating anti-bias training materials on harm reduction.

Aoki said that one goal was to make sure that the employee handbook–and the SFAF policies it shares–uplifts employees with insights about the goals of SFAF, and ensures that employees know their rights and are able to navigate their working situation in the best way.

Empathy, he said, has been at the core of his work.

“I think the central goal of any type of mission for a healthcare organization is to make sure that individuals are able to live their best lives,” said Aoki. “So we have to think about how things like stigma, for example, prevent our capacity to empathize with one another. If we have policies like zero tolerance, or essentially a ‘mandatory minimum’ policy, how do those prevent us from fully assessing the situation a certain employee or client may be in?”

“Our mission within the Employee Engagement team is to root our workplace culture in the same principles that we offer services to our clients with,” said Alex Locust, director of Employee Engagement. “By extending the same support to our staff, not only are we modeling the type of culture that we espouse for service provision, but we are also aiming to set our employees up for success. If we are striving to recruit, hire, and retain staff from our prioritized communities, we have to be mindful of and center the disproportionate challenges they face within working environments steeped in antiquated (read: harmful and violent) workplace policies and procedures.”

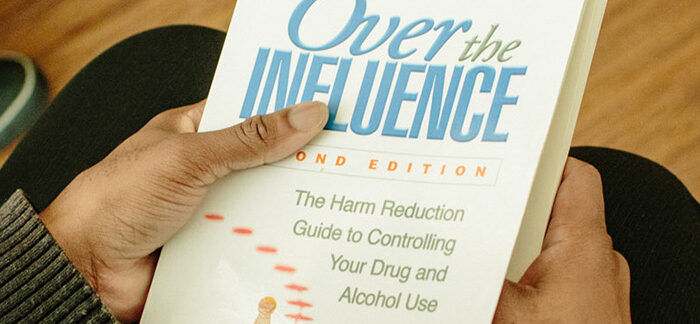

Part of Aoki’s work involved making recommendations on how to revise archaic language around substance use in the employee handbook. For example, taking out references to “drug and alcohol abuse,” since those phrases carry connotations of stigma.

“When we think of ‘abuse’, we think of ‘child abuse, spousal abuse.’ It all sounds very criminal,” said Aoki. “SFAF uses a harm reduction philosophy with clients, and it’s embedded in the mission of the organization. Sending a message that any relationship with substances is ‘abusive’ obscures that harm reduction message,” he said.

In addition to revising language, Aoki researched ways to reframe and revise the “corrective action procedures” for substance use specified in the handbook.

Many workplaces have “reasonable suspicion” clauses in their employee handbooks related to drug and alcohol use. For example, the Society for HR Management, in a drug and alcohol policy template, specifies that “specific observations and behaviors that create a reasonable suspicion that an individual is under the influence” can include: movements (fidgety, dizzy), flushed face, acting irritable or drowsy, or yawning.” These behaviors could lead to an employee being referred to a manager or HR in many workplaces.

At SFAF, the idea is to replace action based on “reasonable suspicion”, which can be based on biases against drug use, with more clear-cut assessments of foundation protocol violations, and assessments of any harm caused.

“There are certain codes of conduct that employees abide by,” said Aoki. “So that’s one thing that needs to be evaluated. And, the second clause is asking about if there was any harm caused. If an employee has tremors, what about that is impeding their work performance? Are they causing harm?”

Tension arose in this work from federal policies that essentially present a “zero tolerance” requirement for workplaces that receive federal grants. Aoki said they had to find ways to stay compliant with these policies, while simultaneously working to reduce the stigma surrounding drug use.

“It’s been interesting to find a balance between these federal guidelines that we have to abide by, and the foundation’s principles and goals around harm reduction,” he said.

Raised in Salt Lake City, Utah, Aoki was unfamiliar with the philosophy of harm reduction until he began volunteering in the court system and learned about the intersections of substance use, systemic racism, inequity, and the war on drugs. He also used high school and college debate as a key learning experience to inform himself about social justice issues.

“I remember that in high school, we had a month-long unit dedicated to abstinence–from sex, but also drugs and alcohol,” he said. “So I was raised in an environment where discussion of substance use was highly stigmatized. But my volunteer experience, and then the work I’ve done in college, has really opened up my perspective to see how important it is to recognize people’s perspectives and backstories to see how that informs what they do.”