HIV stigma–macro and micro

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

The longer I live with HIV, the more destructive that HIV and AIDS stigma seems to be. For some of us long-term survivors, the virus and the medications taken before the advent of HAART (in 1996) have ravaged our bodies for decades.

As we age more rapidly than our HIV-negative peers, we face increased risk of heart disease, loss of bone mass leading to osteoporosis, CMV infection, kidney disease and failure, and other comorbidities. But most of those are, to some extent, “manageable.”

The same cannot be said for the stigma we face for being HIV-positive.

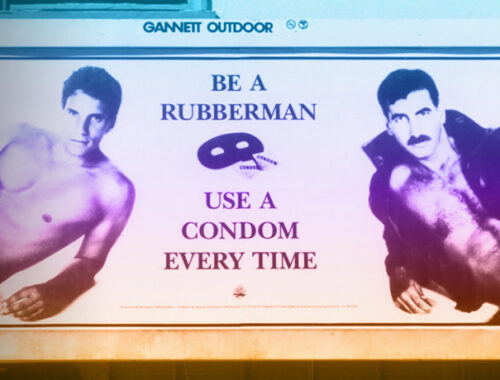

That stigma has taken hold in both widespread systemic forms as well as smaller, more personal forms. Macro and micro, for short. In its widespread macro form, we’ve seen stigma from the very start, with people like William F. Buckley and Senator Jesse Helms calling for all HIV-positive people to be rounded up, quarantined, and tattooed with a plus-sign on our buttocks to warn off potential sexual partners. We saw it also in the rush to criminalize the HIV-positive, with draconian laws based on irrational fear rather than scientific reality; in many states, those stigmatizing and punishing laws are still on the books, still enforced.

In its smaller, more personal micro form, I suspect that all of us living with HIV have experienced small, personal instances when stigma raised its ugly head in our daily lives — from the medical community, from our employers, even, saddest of all, from our friends and our own communities. Having experienced all three, I can attest that the micro forms of stigma are just as painful, frustrating, and damaging as the macro form.

I learned of my HIV diagnosis one July morning in 1989, in Pittsburgh, PA. I awoke with my right eye swollen completely shut and cysts all over my chest and belly. I rushed to the emergency room at Allegheny County General Hospital, where I was immediately pushed into a “biohazard isolation” room. After a week of intravenous antibiotics, the swelling and the cysts were gone, and I was ready to go home. I sat on the edge of the bed waiting for my “exit interview” and dismissal. Three doctors entered and stood on the opposite side of the room, nervously conferring, furtively glancing my way now and then. Finally, one of the doctors approached me on the bed.

“Mr. Trout,” she said, “I’m afraid I have some very bad news. We’ve done a lot of tests and, well, you’ve been infected with the HIV virus. I’m so sorry.” She reached out her hand to put it on my shoulder to comfort me—but jerked it back upon contact as if she had just touched roiling lava.

She hid her hand behind her back, her eyes widening as if to say What the f**k did I just do?! In that instant, just seconds into my life with HIV, I saw that in the eyes of this physician I was now among “the untouchable.” I sensed a future of being treated like a leper escaped from the colony.

Sadly, it was not the last time a physician or dentist made me feel untouchable.

Less than three years later, in 1992, in San Francisco, I applied for a job as a secretary in a medium-sized well-known law firm. In the corner glass-walled office of the founder and head partner of the firm, he interviewed me for twenty minutes or so, and everything had gone quite pleasantly. Then, Mr. Liddell (we’ll call him), a tall, large man well into his seventies, rose from his seat, walked to one of the glass walls and gazed out for what felt like hours. He sat back down and leaned toward me with his elbows on the desk.

“Hank, how’s your health?” he asked. Stunned, I sat, only blankly there for a moment, then smiled at him.

“Mr. Liddell, we both know that you’re not allowed to ask that question. But since you asked, my health is fine. How’s yours?”

Presumption led to that kind of one-on-one micro stigmatizing. Mr. Liddell had presumed, first, that I’m gay—he presumed that a well-dressed and reasonably groomed, single, 40-year-old white man applying for a job as a secretary rather than as an attorney must be gay. And the word “gay” led him to presume that I had AIDS or at least HIV and wouldn’t be around long. Can’t have new employees dying on us.

The fact that he was right (in 1992, having HIV was a death sentence) did nothing to dampen my anger at his presumptive fear of me, at his feeble effort to disguise it. Since he asked me that question, I knew he had asked it before of guys, negative and positive, further spreading the stigma. How many times we have all endured this kind of micro stigmatizing at work—or applying for work.

And then other times, the stigmatizing comes from segments of our own communities. Many of us have not only lost friends and lovers to AIDS-related complications, but also lost friends who freaked out around anyone who was HIV-positive and thus imposed a personal quarantine on us. I first noticed this when a handful of close (I thought) friends drifted away after learning of my serostatus. Before long, I felt the sting of being stigmatized by a larger group within our community.

For many years, I had been an active amateur/hobbyist wrestler and was somewhat well-known to the surprisingly worldwide “underground” of gay and bi men who still like to wrestle beyond high school and college. We used widely distributed resources for contacting other like-minded wrestlers to meet, via personal ads, mail, and telephone in pre-internet days, and then online. I was well-known for several years in that group, with friends whom I had hosted when I was single, and could introduce guys to other wrestlers in the area.

But, as within nearly every group of people, there were bored gossip mongers among us who spread “Breaking News” information about other people’s serostatus, including mine, causing nearly half of those men to sever communication with me and others to refuse to wrestle with me. Like the physician who diagnosed my HIV, members of my own community had reminded me that I was “untouchable.”

Usually when we talk about the stigma of HIV, we talk about the broad, widespread, systemic kind of stigma—the kind that leads to disparities in HIV prevention, testing, and treatment in Black, Latinx, transgender, and rural communities; to disparities in PrEP education and use; to disparities in the quality of health outcomes; and to criminalization and neglect. Those discussions are crucial.

We must do the hard work to combat systemic macro stigmatization of people living with HIV. But we must also be aware of and attentive to the personal slights and shaming of micro stigma, which cuts deep and worsens the PTSD and lingering grief we carry from all we’ve lost in the last forty years. We must confront micro stigma as vehemently as we confront systemic, macro stigma.

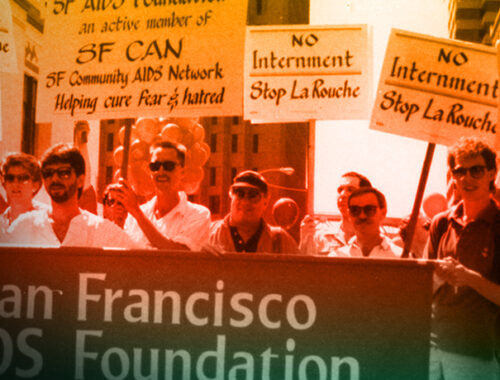

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.