From “risk” to “undetectable”

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

Over 40 years, there has been a remarkable transformation in the understanding and language of HIV “risk.”

From the early years of “gay-related immune deficiency” (“GRID”), recognized as likely caused by a sexually transmitted infectious agent, community members knew that some behaviors were more likely to result in HIV transmission than others. The urgency of being able to communicate which behaviors were most likely to result in HIV transmission meant that many times, our focus centered around “safe” sex and HIV “risk.”

Throughout the years, we have course-corrected this perspective to not only neutralize the state of living with HIV, but to also adapt to the changing context of what it means to live with HIV in recent years with medical advances in testing, treatment, and prevention.

Vince Crisostomo, SFAF’s director of aging services, has seen these shifts in how the public thinks about and describes HIV over the course of the epidemic.

“For a lot of people, all they knew about AIDS was how it was covered in the media,” said Crisostomo. “It was a death sentence, and there was so much stigma. I remember a joke Johnny Carson said in the opening monologue of his show once—he asked, ‘What does GAY stand for?’ And the answer was, ‘Got AIDS yet?’ And people laughed.”

Now, he said, we’ve made changes in how we talk about HIV and AIDS, and many people with HIV and AIDS live openly and proudly with their diagnosis. Even still, stigma associated with HIV and AIDS lives on. “Even to this day, stigma runs deep,” he said. “There’s still work to do to lessen stigma in our communities.”

The beginning of HIV testing

By the spring of 1983, French scientist Luc Montagnier, MD (and soon after, Robert Gallo, MD in the U.S.) had identified the virus causing AIDS–but it would be nearly two years before a test was developed that could test for the virus in blood banks across the country. In March of 1985, an HIV antibody test made by Abbott was approved by the FDA, and test kits were delivered to the first blood bank in the U.S. to receive them–Irwin Memorial Blood Bank in San Francisco. From this point forward, the risk of contracting HIV from a blood transfusion in the U.S. shrank to practically zero.

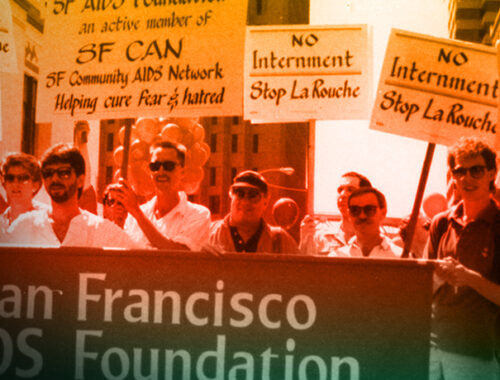

Testing for the virus causing AIDS (then called HTLV-III) in blood samples caused immediate concern and fear among gay advocates and allies about the possible implications for people living with the virus.

A New York Times article from 1985 expressed concern about the civil liberties that could be placed at risk for people who were diagnosed with HIV, saying, “advocates say that the personal trauma of individuals exposed to the AIDS virus is intensified by fears that their test results will be disclosed and that harsh restrictions will be placed on their lives… it is not difficult to imaging a move toward widespread mandatory blood screening and that those with positive test results could face discrimination in jobs, schools or housing.”

“There were many issues around disclosure and having people find out if you had HIV or AIDS,” remembers Crisostomo. “You were treated differently, even here in San Francisco.”

When Crisostomo moved to San Francisco from New York, he faced discrimination in housing because his partner had AIDS.

“I was rejected from an apartment because my partner had visible Kaposi Sarcoma. One of the neighbors said that they didn’t want to come home and see that everyday. When I went to pick up the keys, the landlord wouldn’t give them to me–even though I had already signed the lease,” he said.

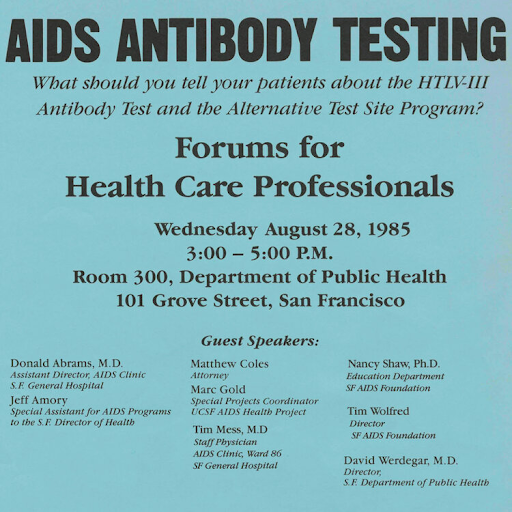

Anonymous testing sites were proposed and implemented by the federal government as a way around issues of disclosure and discrimination, and by early September in 1985, more than 20,000 across the U.S. had accessed an anonymous HIV test through these centers.

“To test or not to test clearly would become the most important personal decision most gay men would make in their adult lives,” explained Randy Shilts, in And the Band Played On. “To be tested meant learning that you might at any time fall victim to a deadly disease… However, not to be tested meant that you might be carrying a lethal virus, which you could give to others.”

“I found out my diagnosis in 1989, and the weight that came with that diagnosis was massive,” said Crisostomo. “Things at that time were so uncertain, and so unclear. Many people just didn’t want to know their status simply because it was a death sentence.”

For those working in public health, the desire for people to know their status in order to make informed decisions about their sexual behavior was balanced by the serious emotional toll that a positive diagnosis would mean.

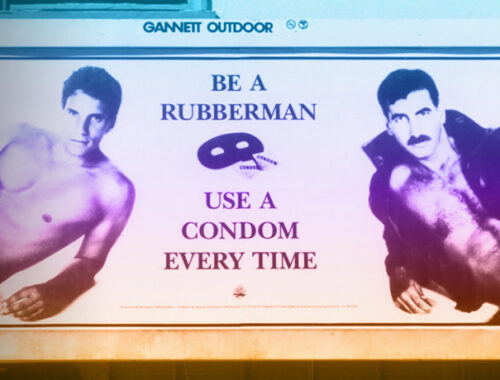

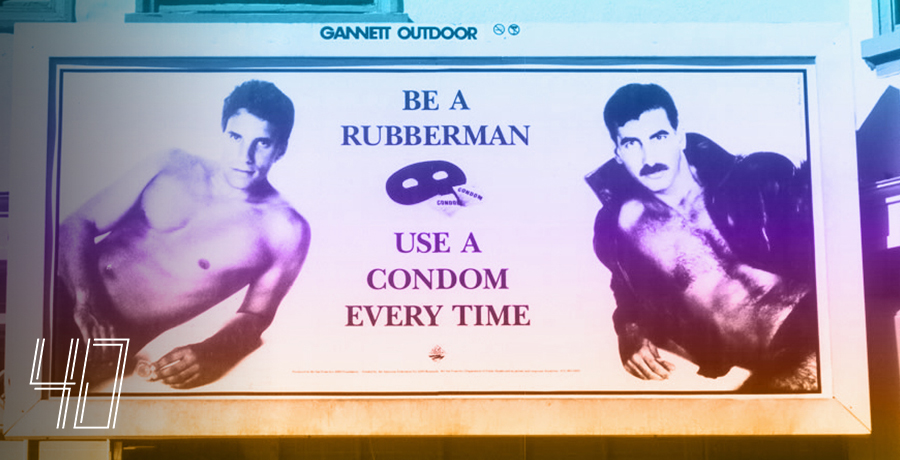

Shilts reports that once tests became available in 1985, SFAF walked this fine line by not promoting testing or not testing for the virus. Instead, SFAF launched an “aggressive” advertising campaign in local newspapers listing the pros and cons of the test, and urging gay men to make up their own minds about whether or not to be tested.

SFAF continued its educational efforts around antibody testing in 1985 by partnering with the Centers for Disease Control to develop materials to share information about anonymous testing for HIV, and the following year produced the nation’s first video and brochure to be used in antibody test programs. SFAF would become known for creating critical AIDS education resources like these in the coming years, being used by health departments and community organizations worldwide.

In the following years, SFAF would spread awareness of antibody testing far and wide, distributing hundreds and thousands of brochures, creating TV ad campaigns, placing paid ads in local media outlets, hosting forums on testing and related issues, and promoting news features and stories about testing.

By 1989 with some advances in HIV treatment, SFAF began to recommend that all gay and bisexual men (and other who may be at risk), consider taking an antibody test.

“The pros and cons (of testing) have changed,” Timothy Wolfred, the executive director of SFAF at the time was quoted as saying in a 1989 San Francisco Sentinel article. “There is now substantial evidence that early detection can slow the progress of the virus.”

To this day, SFAF serves as a resource for HIV testing and information, and we share the message that all people should know their HIV status. We promote regular HIV testing as part of ongoing healthcare.

Undetectable = Untransmittable

The idea that people living with HIV, who are successfully managing HIV with treatment, are less likely to transmit HIV to other people began as early as the mid-1990s. At the time, a so-called “treatment as prevention” approach with pregnant people prevented the transmission of HIV to unborn babies.

As HIV treatments became more effective, and more widespread, there grew to be a greater awareness that anyone living with HIV on treatment was unlikely to transmit HIV to another person. This understanding, however, remained anecdotal, with physicians and public health agencies continuing to urge all people to prevent the spread of HIV by other means, such as condom use and serosorting.

The publication of “The Swiss Statement,” in 2008 by a group of Swiss HIV experts, was the first-ever consensus statement declaring that people living with HIV who are on effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), have a viral load suppressed to <40 copies for 6 months, and do not have any sexually transmitted infections are “non-infectious” for HIV. At the time it was issued, the statement proved controversial.

Without large-scale clinical trial data to provide definitive proof that people living with HIV with suppressed viral loads were not transmitting HIV, top HIV experts in the U.S. continued to urge all people living with HIV to take precautions (i.e., use condoms) to prevent the transmission of HIV.

SFAF executive director in 2008, Mark Cloutier, was quoted by the Bay Area Reporter saying, “I think there’s a little hazard of them putting this out and not adequately explaining what was not known and the unpredictability of abandoning condoms.”

A joint statement by SFAF and the San Francisco Department of Public Health said the report offered “insufficient evidence to abandon safer sex practices,” and that there was concern that the report was based on data only from heterosexual couples, and that it didn’t take into consideration the possibility of viral load spikes and resistance developing to treatment drugs.

It wasn’t until 2011, with the publication of results from a study named HPTN 052, that the HIV community had definitive proof that treatment as prevention works–at least for heterosexual couples. HPTN 052 was designed to answer two questions: First, is it better for people living with HIV to start antiretroviral therapy right away for health reasons? And second, can antiretroviral therapy that suppresses HIV replication prevent the sexual transmission of HIV? The answer to both of those questions, the study found, was a resounding YES.

Additional studies provided evidence in 2016, 2017, and 2018 that treatment as prevention works for men who have sex with men (and anyone living with HIV)–and that condomless sex with a person living with HIV doesn’t result in HIV transmission if the person living with HIV has an undetectable viral load.

Because results of these studies were released in medical journals and HIV conferences largely attended by physicians and researchers, news of this important understanding didn’t reach lay audiences until an advocacy group, led by activist Bruce Richman, launched a campaign under the name “Undetectable = Untransmittable,” or “U=U.”

“When I was diagnosed with HIV in 2003, I felt like I was a walking infection,” Richman told BETA in 2017. “I was terrified about passing HIV on to someone that I love. I didn’t start treatment because taking a pill every day would remind me that I was infectious, every day. After I started treatment in 2012, when my health started to deteriorate, I learned from my doctor that because I was undetectable, I couldn’t transmit HIV. I couldn’t pass it on. I was elated.

“But very soon I became outraged. Because every HIV treatment site, every media outlet, every ASO, every federal health department, every state health department, everywhere, was saying that I was still a risk. And millions of people with HIV were still a risk. It was clear, for many reasons, that the breakthrough science wasn’t, and still isn’t, breaking through to the people it was intended to benefit. It wasn’t accepted or understood outside of well-informed medical and public health communities.”

SFAF adopted information about U=U during this time, joining the U=U coalition and sharing out the message to our community. Now, the empowering message of U=U is accepted and used globally by the medical, scientific, and public health community.

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.