From Awareness to Activism

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

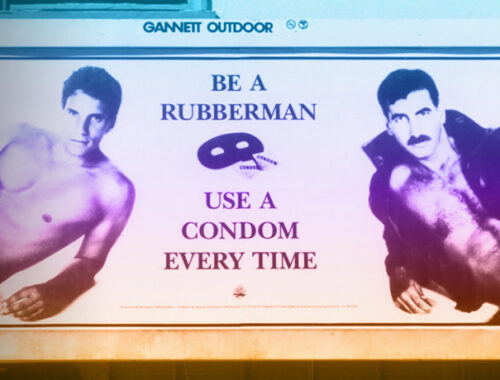

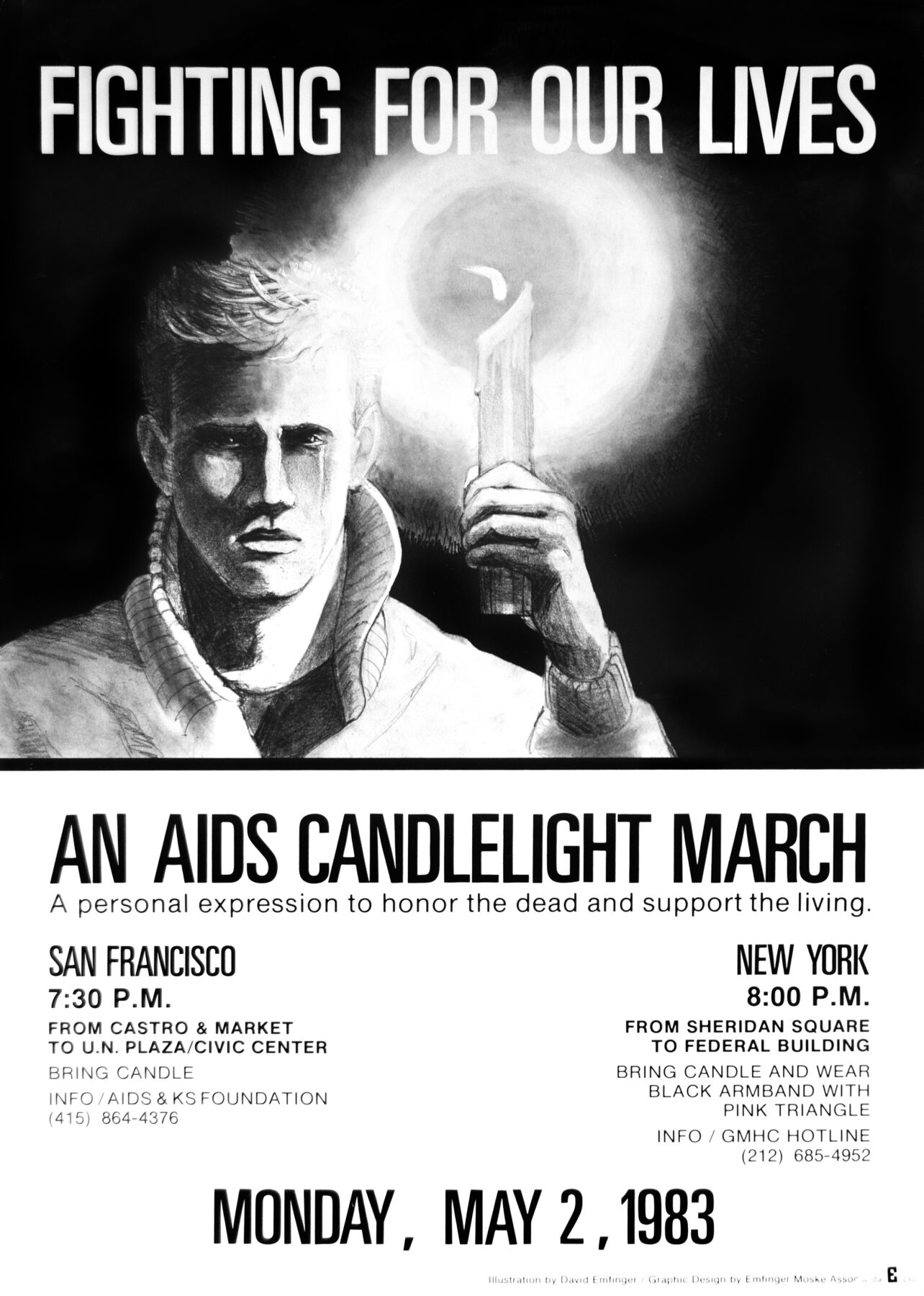

On May 2, 1983, more than ten thousand people living with HIV and their supporters marched down the streets of San Francisco from the Castro to Civic Center. Organized by the AIDS & KS Foundation (which later became San Francisco AIDS Foundation), this public display of solidarity drew attention from around the world to a crisis that had not yet been publicly acknowledged by the U.S. president at the time.

“I remember much of the march being pretty somber,” said Michael Helquist, a former AIDS reporter for the local LGBTQ publication Coming Up. “There was this sense of shock, like, ‘How could this be happening?’ I remember looking back on Market Street, and just seeing this sea of candles. It definitely had an effect. There were marches held in other parts of the country–some were truly memorials and some were more activist-oriented. San Francisco’s was an interesting mix of both. There was definitely a wish for a way for the community to come together in a way that would be healing, and there was also a demand for something to be done.”

Helquist remembers that the march was part of a week-long set of events named AIDS Awareness Week–organized to call attention to the growing crisis and mobilize support for people with AIDS. Although the march was largely silent, a speaking program held at UN Plaza immediately afterwards brought people with AIDS to the stage.

“There were five or six people with AIDS that spoke,” said Helquist. “They gave voice to what people were feeling. In the sense of, ‘We’re really angry about what is happening to us.’ They were 20 and 30 year olds–about to die. A diagnosis in those days was a death sentence. We were angry, we were sad, and we wanted to be supportive of the guys who already had this.

“This was many years ago, but the memories that stay with me are of the people with AIDS who spoke,” said Paul Boneberg, a long-time San Francisco resident who attended the March and Vigil. “I remember in particular Mark Feldman, who was the principal speaker. He was very sick at that point–and the remarks he gave were very powerful, and very poignant.”

Boneberg said he remembers the early, grassroots organizing that led to a very successful and visible Vigil and March. “There wasn’t a tight agenda. I remember someone said later that we didn’t even know if anyone would show up. You have to remember, that time, that people were afraid of people with AIDS. But there were two profound things that came out of this. First, the community showed up and said, ‘We’re not afraid–we’re here for you.’ And second, people with AIDS stepped up and said, ‘We want to lead.’”

“We did come together, we were scared together,” said Helquist. “And there was some strength in that. We wanted to challenge the President, and Congress. To say, ‘We won’t put up with this.’ And we knew we had political power in the city–and we’d be using that. We just didn’t know how big AIDS was.”

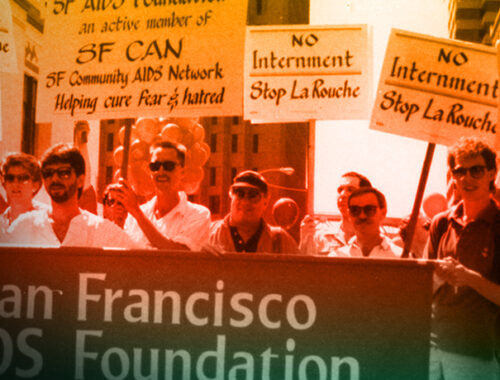

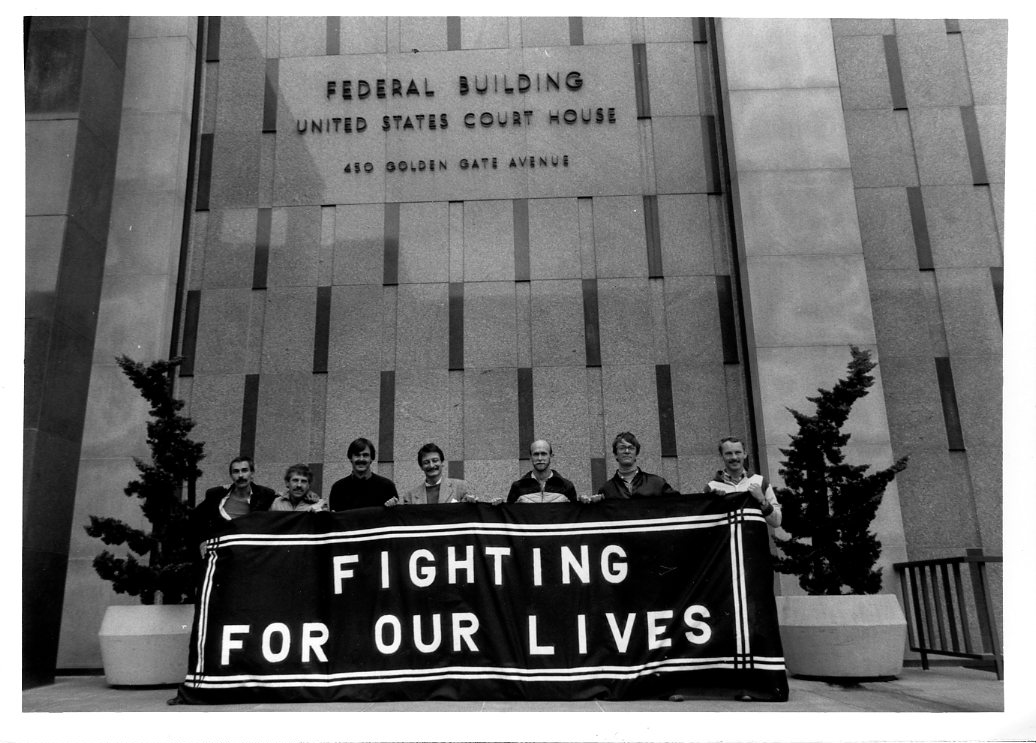

Rallies, demonstrations, and marches are important ways that San Francisco has raised awareness and a sense of urgency to act. From this very first moment when people with AIDS came together in public demonstration, the momentum of the Movement hasn’t stopped. Over 40 years, our community has rallied and spoken up to bring about critically-needed change.

“We need to get Washington to care about us”

Since 1990, the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act has brought billions in federal funding to hard-hit cities and states to ensure that all people living with HIV are able to access the HIV resources, medications, and services they need. To this day, this successful legislation has been reauthorized by Congress four times and continues to provide a critical safety net for lower-income people living with HIV and AIDS.

This impactful legislation has its beginnings at San Francisco AIDS Foundation, at our former office on 25 Van Ness. And its existence is thanks to powerful advocacy efforts by our senior leaders and leaders of other AIDS organizations in the late 1980s and 1990s.

“I remember a small group of us meeting to figure out how to get the federal government to put money into AIDS,” said Pat Christen, who served as SFAF’s executive director from 1989 to 2004. “It was such a desperate and difficult time. Healthcare burdens in cities–especially San Francisco, LA, Boston, and New York–were just staggering. I remember we had this realization that if we didn’t do anything about this, Washington was not going to come to our rescue. Washington didn’t care about us. We needed to get Washington to care about us.”

Tom Sheridan, who became the chief architect and lead strategist behind the enactment of the Ryan White CARE Act, along with Tim Sweeney from the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and John Mortimer from AIDS Project LA brainstormed with Christen ways in which the federal government might direct funds to cities across the nation. Christen proposed modeling the funding after disaster relief, which ultimately helped shape the form of the legislation.

In testimony before a House of Representatives committee in 1990, Christen said, “Epicenters of this disease must be considered natural disaster areas and be eligible for the type of emergency funding we would afford a drought in Kansas, a flood in Texas, . . . an earthquake in San Francisco. AIDS should be considered no less a natural disaster than any of these other tragedies . . . In the same way that we spread the cost of the drought, flood or earthquake over the whole population to assist those regions hardest hit by such anticipated disasters, we must also spread the cost of AIDS over the entire nation.”

There was broad support for the bill and a big push from SFAF leaders and activists across the nation to get the bill signed into law. SFAF played a leading role in the development, organization, advocacy and media outreach to encourage its passing. Senator Edward Kennedy, lead author of the bill, named the bill in honor of Ryan White, the Indiana teen who died of AIDS in April of that year. Ryan’s mother, Jeanne White, advocated for the passage of the bill in Washington along with celebrities including Elizabeth Taylor.

The bill was ultimately signed into law on August 18, 1990, and SFAF has remained a leader in each of its four reauthorizations.

“The legacy of the Ryan White CARE Act is absolutely the most important thing that San Francisco AIDS Foundation can hang its hat on,” said Ernest Hopkins, Senior Strategist and Advisor at SFAF. “We can say that we were integral in making that happen. The Ryan White Care Act has provided countless billions of dollars to Ryan White programs and jurisdictions since it passed in 1990.”

Fighting for fair legislation for people with HIV and AIDS

Although the earliest years of SFAF were focused on providing direct services and information for individuals with HIV and AIDS, attention quickly turned to the larger context. In 1987, SFAF founded a Public Policy department focused on advocating at the local, state, and federal levels for humane policies to address the growing crisis.

Working in coalition, the team was successful in the ‘90s in advocating against stigmatizing and harmful laws and policies such as those that called for mandatory tracking and reporting of people living with HIV, HIV criminalization laws, and bans on AIDS education in schools.

Hopkins remembers SFAF’s policy and advocacy work that transformed the harm reduction movement. In 1993, SFAF crafted emergency legislation for syringe access and needle exchange, renewed every 90 days, which effectively legalized the distribution of new syringes and harm reduction supplies to people injecting drugs.

“It was a really big deal,” he recalled. “The process the foundation developed served as a model across the country. And when I joined the foundation, we were working closely with amFAR to push these legislative models out across the country. We wanted to make sure that people knew how to craft the language for an emergency order, knew how to do the renewals, and also knew how to work with police and health departments. This work moved harm reduction from the periphery to being sanctioned by the health department and police.”

Policy leaders at SFAF continued to shape federal policy decision-making. SFAF staff helped lead the National Minority AIDS Initiative in 1998, and ensured that HIV was properly represented in the Affordable Care Act in the late 2000s.

“There isn’t much that’s happened that we haven’t been integrally involved in, quite frankly,” said Hopkins. “I think the reason we were able to have credibility to work on so many issues at such a senior level was because of the early work that was done. There’s awareness that we were involved in the creation of the CARE Act, and that we championed needle exchange.”

SFAF continues to this day to work at every level of government to fight for funding and policies that support people living with and at risk for HIV, LGBTQ+ communities, people who use drugs, and others in our communities.

Grassroots organizing is key to building power within our communities and fighting for fair laws and budget initiatives that prioritize the needs of our communities. The HIV Advocacy Network (HAN), is a local group of activists and advocates fighting for our communities on issues related to health justice, harm reduction and drug user health, HIV and aging, housing and homelessness, and intersectional solidarity.

Recently, HAN members organized around the MPX (monkeypox) response in coalition with other community organizations and political clubs, demanding a greater response to the growing crisis. HAN members waited in vaccine lines with community members for hours, talked to them about their concerns and frustrations, and recruited them to take action. Together, HAN members and the community fought for better access to vaccines, more streamlined options for treatment and care, and increased transparency and accountability from city, state, and federal governments around their responses.

“When we organize, we win–and that’s why it’s so critical to get involved in the fight,” said Ande Stone, senior community mobilization manager. “Decision-makers and political leaders are making decisions that impact our lives. If we don’t demand better solutions, it’s easy for our concerns to be overlooked. This leads to a real impact on people’s health and their lives. HAN empowers us to come together collectively and make our voices heard. It gives our communities real ways to be engaged in the issues they care about.”