A reflection after 40 years of HIV

It’s almost inconceivable that it’s been 40 years. On June 5, 1981, the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) published a summary of five “active homosexuals” who had been treated for a rare type of pneumonia in L.A.–the first report of what would come to be known as AIDS. We have lost so many lives–more than 30 million people worldwide–over the past 40 years.

Now, as we commemorate this somber anniversary, it’s a time to remember the many people we have lost, and also the history that should not be forgotten. It’s impossible to capture all of the history–but here is a bit of my own: The first time I saw the infamous MMWR, the call I got from Dr. Marcus Conant about patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma, and all that led up to the founding of San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

In January of 1980 I was hired by the Speaker of the California State Assembly to work as a legislative assistant for the Democratic Caucus and moved from San Francisco to Sacramento. I was 25 years old, politically ambitious and excited by the career opportunity. I had been recommended for the position by then-Assemblyman Art Agnos, who would go on to be Mayor of San Francisco. Ironically, Agnos had defeated my first mentor, Harvey Milk, many years earlier in a bitterly contested race to represent the city’s 16th Assembly District.

I was assigned to the Assembly Health Committee where my job was to analyze bills and advise Democratic committee members. Most of the legislation was not controversial but there were occasional hot-button bills. I also wrote speeches for several members. With no real previous background in public health issues, I spent every free minute reading and studying the various public health journals that would arrive by mail in our office every week. Among them was the “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report” from the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta.

I was homesick for San Francisco and couldn’t afford a car so most Fridays I would take the Greyhound bus back to the bay and return to the Capitol on Monday. That first week of June I got back to the office and began leafing through the stack of periodicals on my desk. I glanced at the cover of the June 5 issue of the MMWR and my eyes were caught by the first sentences of the first article: “In the period October 1980 – May 1981, 5 young men, all active homosexuals, were treated for biopsy-confirmed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia at 3 different hospitals in Los Angeles, California. Two of the patients died.” I clipped the article and tacked it to the cork bulletin board over my desk.

The next day I read the article again and again, searching for some clue in the detached, emotionless dry text. There were none. That night I couldn’t sleep. I kept remembering fragments of conversations I’d heard over the past several months about other young men around my age who were sick with some sort of pneumonia or meningitis, or diseases I’d never heard of before. One month later, the New York Times ran an article headlined, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” describing clusters of gay men in New York City and California who were suffering from Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumocystis carinii.

Later that summer I returned to San Francisco to work in the district office of Assemblyman Agnos, whose district included Castro Street, South of Market, Polk Street, Haight Street and other neighborhoods with large numbers of what are now known as LGBTQ people. Agnos served on the powerful Ways and Means Committee, which controlled state funding. That would be the reason I got a call from Dr. Marcus Conant, a dermatologist at the University of California Medical Center in San Francisco. Dr. Conant had patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Dr. Conant took me to dinner at the Zuni Café and calmly laid out his theory about the growing number of cases. He thought it was probably caused by a previously unidentified virus, that it was likely transmitted through sexual contact, that it acted to cripple the body’s immune system and that, if treatments were not discovered, would be fatal. I said, “If you’re right, then we’re all going to die.”

I talked to my boss the next day. The son of Greek immigrants, Art Agnos had worked hard to gain the trust of the gay community after the bruising race against Harvey Milk, introducing legislation to protect people from job discrimination based on sexual orientation. Harvey had been murdered just three years earlier, homosexuality was still illegal in most states and public opinion about LGBTQ people was overwhelmingly negative. Agnos listened to my fears and told me to take whatever time I needed to do whatever we could to identify this new threat and organize to meet the challenge. Dr. Conant insisted that this would require the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars and the creation of social and medical infrastructure that was inconceivable at the time. “We’re going to need a foundation and clinics to fund research and care for patients. This thing is spreading, there’s no time to wait,” Dr. Conant repeated his message to anyone who would listen.

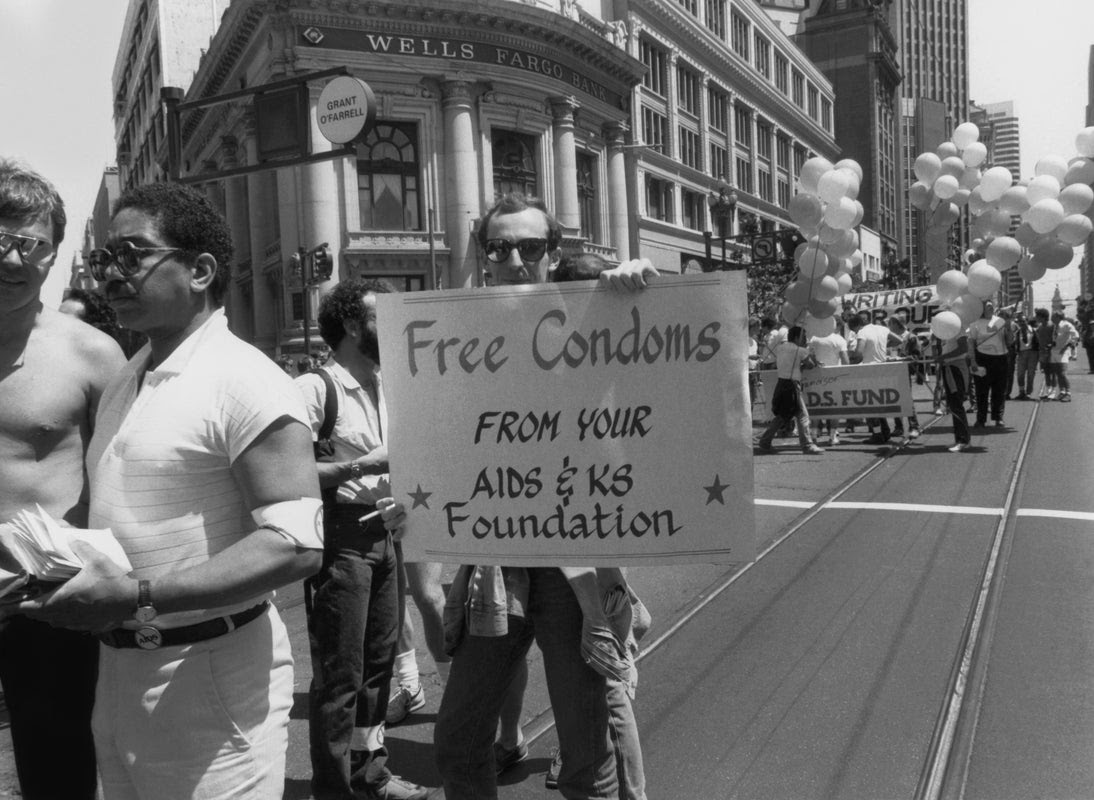

Dr. Conant, joined by Dr. Paul Volberding from San Francisco General Hospital and others started the Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research and Education Foundation in the early months of 1982. We rented two small rooms one flight up in the 500 block of Castro Street. I remember the day our phone was installed. The telephone company technician left and the phone began to ring. Four decades later it’s still ringing.

By 1985 it seemed that almost everyone I knew was dead, dying or caring for someone who was dying. The KS Foundation became the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. We marched, lobbied, ACTed UP, sewed quilts, raised money, got arrested, confronted politicians, transformed medical research, cared for the sick and comforted the dying. We did everything we could to fight the disease and defend the communities that were under attack. It was a time of appalling loss, terror and misery and yet – somehow – we rose to meet the challenge.

This is what I’m reflecting on today as we commemorate the 40th anniversary of the first documented cases of AIDS. I hope you, as well, take time to reflect on everything we’ve lost–and also what more needs to be done to fight HIV in this day and age.