Artist Ken Jones’ story with Black Brothers Esteem

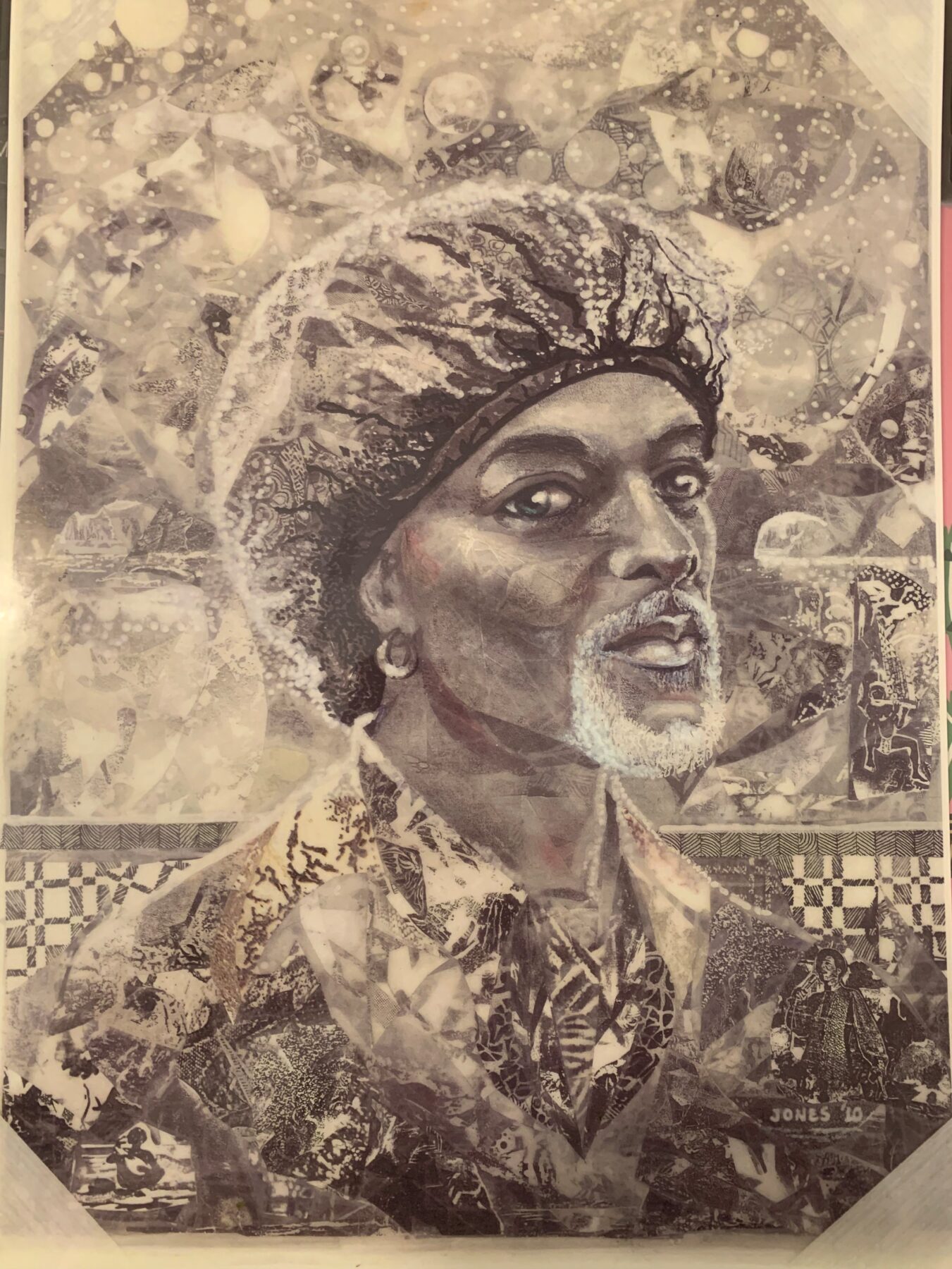

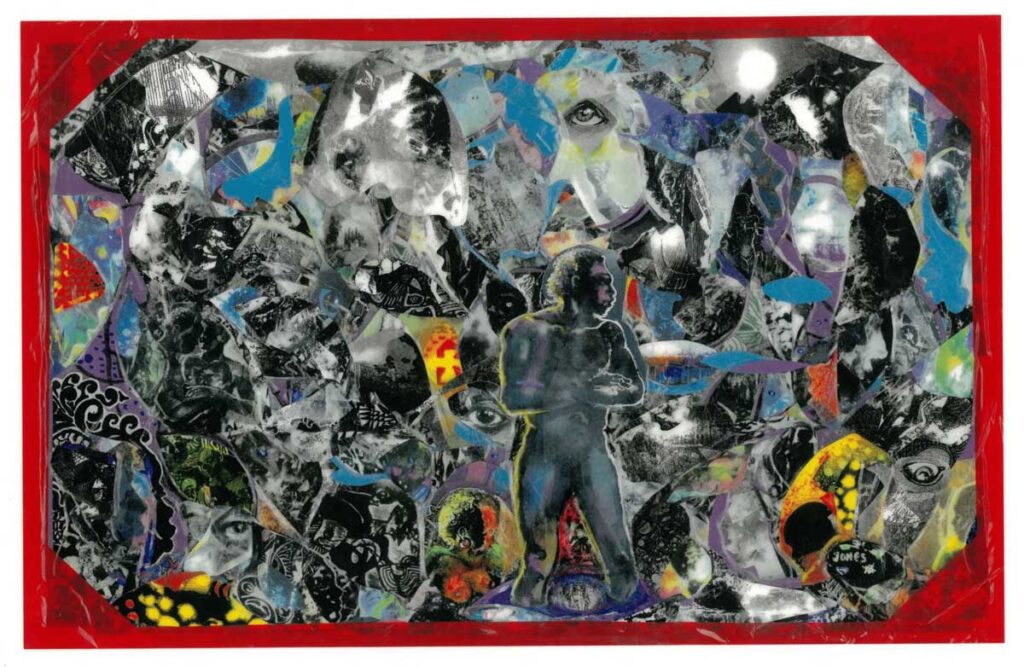

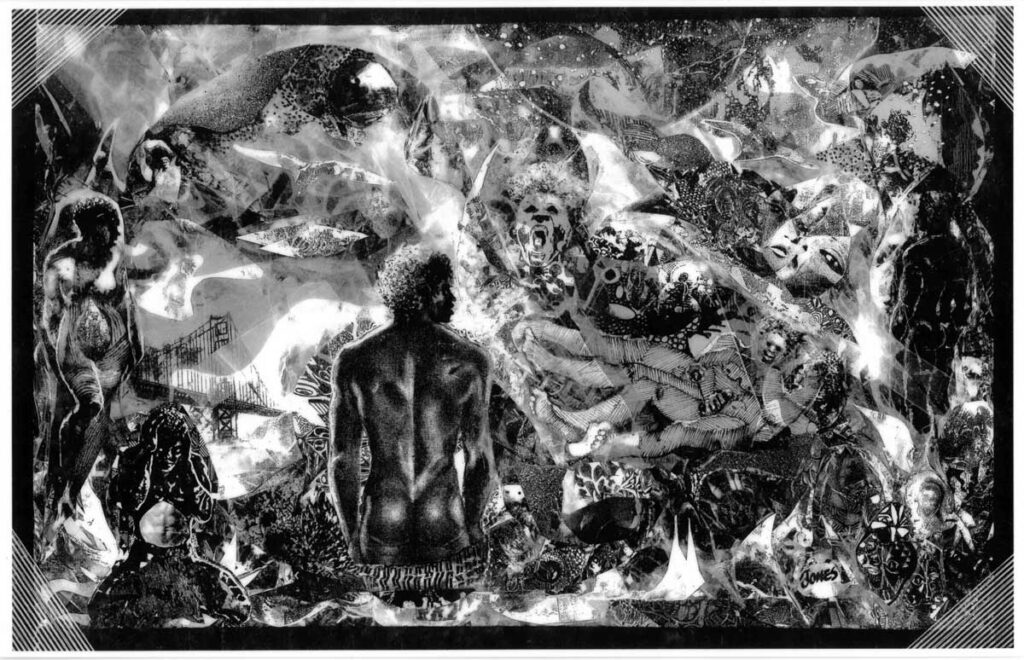

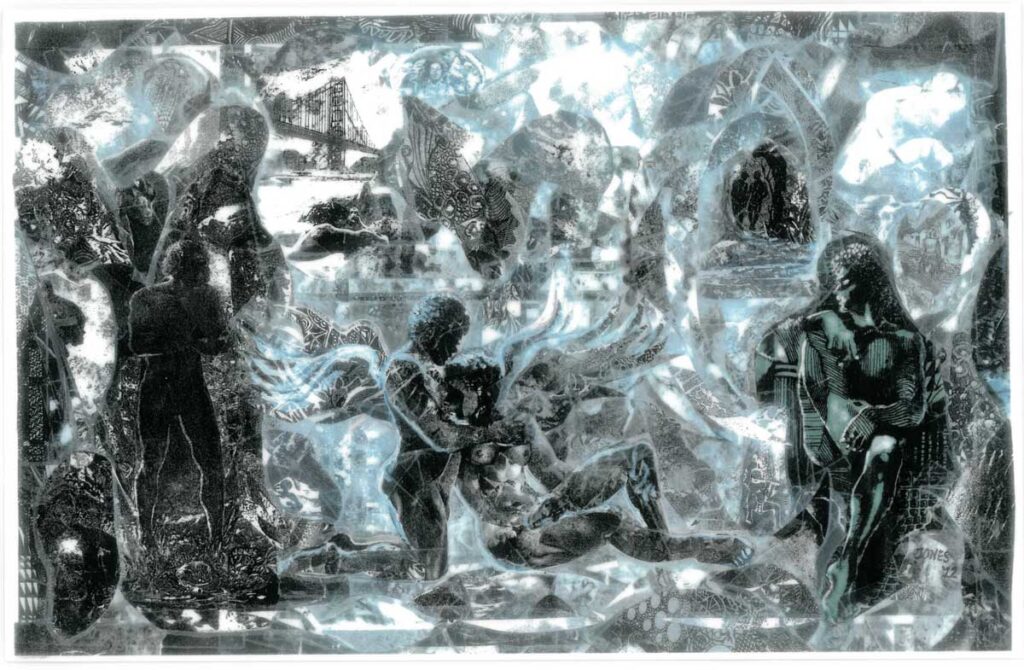

Ken Jones is an artist living in San Francisco, and a proud member of BBE. He invited BBE staff into his home to share more about his life and his involvement in BBE over the years. Before the interview began, he gave a tour of his house, which is adorned from wall to wall with his artwork–collages with vividly rendered scenes, symbols, and silhouettes and portraits. Ken started a cassette tape of a young man singing jazz in a sultry voice–he said that the man singing is him, and began to tell us of his earlier years in music.

“I was 12 years old,” Ken began. “And I shared the stage with those kids that got so popular? The Jackson 5. We were on a talent show together, in St. Louis, Missouri and they was tearing up the stage. They won first prize and I won third. I sang with ‘The Ray Charles” Ken continued, “before he got famous, the Expressions, Sam Cooke… We all used to sing in the Chitlin Circuit in the Midwest.”

Because Black people were not allowed to perform in most nightclubs due to segregation, Black artists were relegated to performing only in certain establishments and on specific nights. This network of venues that allowed African Americans to perform when no one else would ran through cities including Saint Louis, Kansas City, Chicago, and Detroit. It was called the Chitlin Circuit.

Ken sang with Ray Charles, before he got famous, the Expressions, and Sam Cooke.

Ken grew up in Saint Louis, but ran away when he was 16 years old.

“I saw this sign in the window that said, ‘Come to God’s country.’ I thought, ‘I want to be where God was…’ So, I worked really hard, doing drawings for people and so on… Saved my money, and when I got enough, I left Saint Louis.”

Eventually, Ken moved from St. Louis to Los Angeles to find his mother.

“She found me living with these gay guys that had been married for 17 years. They didn’t have any children, and they sort of took me under their wing. When I got to California, the first thing I find out, was it’s possible for two men to love one another. Oh, I was fascinated, and they couldn’t get me back to St. Louis ever again.”

Ken made his way to San Francisco and found, not just a home, but family. “I like being around my people. And me being a gay person, it was gay men.”

Ken has a straightforward approach to solving problems that life brings.

He said, “You have to keep it real. Even though you got a problem, until you face it, you claim it for yourself. Trouble’s out there for anybody who wants to claim it. You hear people say, ‘My trouble is,’ or, ‘His trouble is,’ And they’re giving trouble away, you understand? But you don’t have to accept it. Just because they give it to you, you don’t have to accept it.”

Ken said that he helped to design panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

“This is my art, and my history too,” he said, showing us his work station surrounded by art supplies and drawings. An artist, Ken continues to make art to this day.

He said, “It’s up to me to keep me happy and keep me sane. So I play around, that’s what you’re looking at when you look at my artwork. I’m having fun. I’m not waiting for somebody to come in and bring me fun.”

Ken describes his artwork as different than “commercial” art, since it’s a method of self-expression that may not translate well to others and can’t be taught in schools.

“The only time I had any luck with my art is when I had my shop with my lover up in Haight. Those were “Hippy times. I was a hippy—we were hippies. That went on from ‘65 to ‘72 when the big gay procession from the Haight came over the hill and settled into what is now Castro.”

He described a time when he tried to join an artist group with eight other Black artists, who lived in his neighborhood on Hayes Street in San Francisco.

“I went down, showed them my work, and they didn’t want to have nothing to do with it. They didn’t want me in their club.”

Ten years later, one of the club members came into the club where Ken worked.

“He said, ‘I bet you wonder why we never wanted you in our group.’ And I said, ‘Well, it has occurred to me.’ He said, ‘We just didn’t understand what you were doing. I’ve never seen anything like it. It scared us.’”

Even in San Francisco Ken could not escape racism, prejudice and segregation. “My hang out was The Pendulum, ’cause it was all Black. 90% Black,” he said.

“When people started marching and complaining about freedom and equal rights, the city integrated. They said, We’ll fix it, we’ll shut down all the black bars and make everybody go to the one bar, white bars. That’s how they did it. So, if you wanted to go to a Black bar, you had to go to Oakland.”

His art is a mixture of surreal, impressionist, and stream of consciousness. “My art is my attitude. I don’t know nothing else. It’s just self-expression, that’s what it is.”

Ken said the one time he did have luck with his art was when he had a shop with his lover in the Haight. “It was hippy times. I was a hippy – we all were hippies. That went on from ‘65 – ‘72.”

Ken remembers the transition in San Francisco, when bars catering to the Black community began to shut down. Then, he said, if you wanted to go to a Black bar – you had to go to Oakland.

When Ken joined BBE at San Francisco AIDS Foundation, he found Black community in San Francisco spaces. He said, “I saw a lot of promise and anything that’s gonna help people, I’ll work for. And I’ll do the best I can. That’s all I can do.”

Ken found his way to BBE at San Francisco AIDS Foundation, where he volunteered. He also created art for BBE, which he still has to this day. Sitting at the BBE resource table, Ken helped out when people would come in to learn more about BBE. When people needed Brother/Sister time, he was always there.

“The practice was, If anybody had a problem in the room… You could stand up and state your problem and then they would go around the room and see if anybody had anything to say to help you with that problem.”

Jones remembers one day, leaving a meeting and being followed for a few blocks.

“Every time I turned around to look behind me, he would turn and look into the glass windows or some little shops along the way down the old Market St. I walked up to him and said ‘hey bro, what’s going on?’ He said, ‘I just need somebody to listen to me. Nobody listens to me.’ I took him, bought him a hamburger and a coke, and I let him talk for half an hour. When he got through. I said, ‘Okay, why are you trying to hurt the people you have back home?’ ‘Cause they hurt me’, he said. “Look at it, I said. You survived. You won that war. Why are you still fighting that war? They’re going on with their life and you’re still hanging on to that hurt. You’re just hurting yourself. That’s the way life is. People don’t wanna face it.” You have to keep it real… What’s freedom of all about if you can’t be real? You still running around not admitting things you do, if you are sneaking and doing it… You’re still doing it” Ken laughs.

“You know if you keep it real, be honest with yourself. If you did it–you’re big enough to do it, you ought to be big enough to own up to it, I always thought. But I wish I had somebody to tell me. What I was trying to tell other people, when I was coming up, but I had to learn firsthand by myself.”

“What inspired me to work with BBE was BBE itself, and the promise of BBE. I saw a lot of promise in anything that’s gonna help people. I learned how to deal with another person’s difficulties. You know, embrace one another. Share it, be kind. Every day I pray for kindness, I pray for empathy.”

“I love you guys. That’s why I did it, that’s why I was there. That’s what kept me there for six years.”

It’s a beautiful life. Beautiful life. If people would just be honest with themselves. And these churches going around, one being better than the other–that ain’t nothing. Everybody’s trying to go to the same place. One god. Everybody’s trying to get there.

The interview ends with laughter. Ken looks at us with a smile on his face and says “Love one another. Embrace one another. Share it, be kind. Every day I pray for kindness, I pray for empathy.”