The HIV and AIDS pandemic will spiral beyond our control

In a rousing, and at times emotional, opening plenary session, Chris Beyrer, MD, MPH, from the Duke Global Health Institute, set the stage for a Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2025 that called attention to the global disruptions in funding and services for people living with and affected by HIV set in motion by the Trump administration.

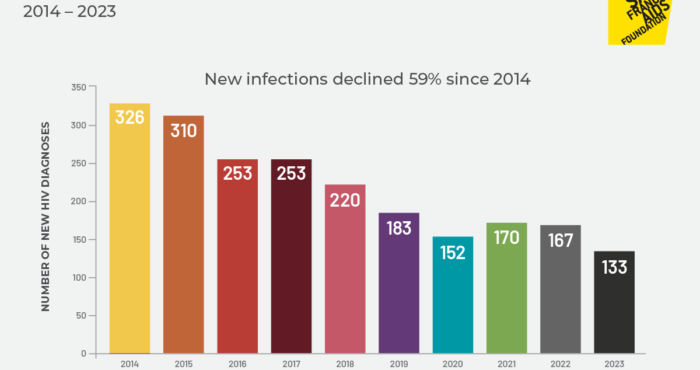

Beyrer gave an insightful review of the landscape of global HIV prevention, treatment, and care in the years leading up to the new Trump administration, making the point that globally, although there has been significant progress, we haven’t been on track to rein in and end the HIV pandemic worldwide. Recent changes to PEPFAR and UNAIDS will only erode the hard-won progress we’ve made.

Reading a quote from a PEPFAR-supported African research investigator, Beyrer shared, “It’s chaos.” This was accompanied by a photo of a USAID outreach medical tent which had been re-purposed in recent weeks as a tent to sell hats.

“The most affected people will be in the poorest countries, and of course, the most marginalized populations,” he said.

Some regions of the world and some subpopulations affected by HIV have made incredible progress in recent years in preventing HIV, facilitating easy access to testing and treatment, and ensuring that people living with HIV are able to live long and healthy lives. But this progress has been uneven worldwide, affecting global 2025 targets to end the pandemic.

As estimated in 2023, nearly a quarter (23%) of all people living with HIV worldwide are not on antiretroviral treatment–far below the 95% target set for 2025. Mortality and deaths due to AIDS were declining, but “not quickly enough,” and the number of new HIV infections per year far exceeded the goal of less than 500,000 per year. Three regions–eastern Europe, Central Asia, and North Africa–have HIV epidemics which are still expanding, and for the last three years, Latin America has also moved into an expanding epidemic.

“In the continued scenario, as though nothing had happened to PEPFAR or USAID or the Global Fund, prevalence [of HIV] is going to continue to rise and be stable until about 2050. So there is no scenario in which we are not going to be treating millions and millions of people for decades to come,” said Beyrer. “We were around 1.3 million [new infections per year], and we know that is an underestimate. A number of countries, most particularly Russia–a very big country with a very big epidemic–has published that they think they only report on half of new infections.”

These estimates are born out by data. In HIV clinical trials, oftentimes conducted in high-incidence regions of the world such as sub-Saharan Africa, researchers are able to measure baseline HIV incidence among participants receiving placebos in prevention and vaccine trials. Beyrer referenced studies such as the ECHO study, which found an “extraordinarily high” incidence of HIV among women in the trial of over four per hundred person years, which translates to a lifetime acquisition probability of one in five women.

“This led us to ask the question, ‘Are we on a trajectory (which is what the global consensus had been) to ending AIDS as a public health problem by 2030?’ And we, with a large group of colleagues, including many from HVTN, we interrogated this and unfortunately came up with a ‘No.’”

The good news, said Beyrer, is that 2023 and 2024 were “the two best years we’ve ever had for oral PrEP.”

“There’s a tremendous increase in PrEP starts with oral PrEP globally, and a great deal of that is due to PEPFAR.”

There are a few problems, though, which have led to challenges in HIV prevention. First, some regions of the world (such as Central Asia and Eastern Europe) haven’t scaled up PrEP programs. “The PrEP era there effectively has not begun. We are not implementing effective prevention where it’s needed most,” said Beyrer.

Another challenge is the sheer number of people you need to reach with PrEP to effectively tamp down all or most new infections.

Beyrer pointed to research by Shook-Sa Rosenberg showing that in order to avert 95% of HIV cases among women in 15 countries in Africa, you’d need to have 66% or 80 million people on PrEP.

Rosenberg’s analysis for men in Africa was similar: to prevent 90% of cases you’d need to have 41% (or 50 million) people taking PrEP.

“You might think of this as something like the limits of PrEP. It will never be what a universal vaccine or universal immunization is.”

The Loss of PEPFAR

What may happen as the U.S. defunds PEPFAR? The impacts will be no less than devastating. Beyrer shared results from an analysis done in 2023 showing that there will be a 400% increase in AIDS-related deaths worldwide from 2024 – 2030, with a resulting doubling of orphans from AIDS deaths during the same timeframe.

One analysis found that a 90-day pause on funding over 12 months would result in 100,000 excess lives lost and 135,000 perinatal transmissions of HIV.

Beyrer shared that currently, 91% of PrEP starts globally go through PEPFAR-funded organizations, which means that most global PrEP use is threatened by this funding pause.

One analysis by Peter Vickerman found that in a year, removing PEPFAR funding for PrEP in sub-Saharan African countries would result in a 30% increase in new infections among female sex workers, a 20% increase among men who have sex with men and transgender women, and 15% among people who inject drugs.

What are the ways forward?

“First of all, we really have to restore PEPFAR and its prevention program. That is fundamental. We have to support the key populations, clinics, and communities because they are the most vulnerable, they’re already closing in many countries. We have to restore the HHS functions, of course, including the NIH, the CDC and the FDA because, as I’ve shown you, I hope without a vaccine and a cure, we are going to be at this well beyond 2050. And of course, we have to do what we’ve been doing for 30 years, which is uphold the human rights of everyone living with HIV and everyone affected.”