The bathhouse battle of 1984

This article was produced in honor of San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s 40th anniversary, which we are commemorating in 2022.

In the early 1980s, as AIDS began to decimate the gay community of San Francisco, a battle broke out over the role that gay bathhouses might play in the spread of HIV. On one side of the battle stood Mayor Dianne Feinstein and other politicians, Dr. Mervyn Silverman, the San Francisco Department of Public Health, journalist Randy Shilts, Larry Littlejohn and a handful of anti-sex crusaders who wanted the bathhouses shut down permanently. On the other side stood the gay bathhouse proprietors, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, a handful of politicos, the gay press, and most — but certainly not all — of the gay community.

To understand the deeply felt antagonism to closing the baths, it’s helpful to understand gay history and the role the baths played in the lives of gay men the world over. In the 1950s and ‘60s, bathhouses existed in just about every major city, but they were operated very clandestinely, sometimes in the basements of hotels, sometimes in the most potentially dangerous neighborhoods. This suited most of the deeply closeted patrons of those years.

But in the post-Stonewall 1970s, gay life came kicking and screaming out of the closet. “Out of the bars and into the streets!” became our rallying cry. Gay magazines proliferated; gay businesses thrived; gay artists and musicians began achieving mainstream success. But most importantly, as individuals we came roaring out of the closet, declaring not only our civil rights, but also the right to a healthy, varied, and abundant sex life. Accordingly, as gay men stopped denying their sexual urges, the bathhouses thrived.

No wonder then that when the City wanted to close the bathhouses, it was seen by many as an anti-gay, anti-sex — an attempt to drive us all back into the closet. The debate became a tug-of-war between notions of public health vs. gay civil liberties, of AIDS hysteria vs. good science and good policy.

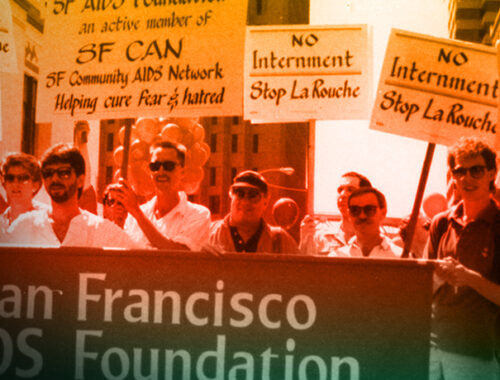

An April city ordinance went into effect banning ”unsafe” sexual activity at sex parlors and bathhouses. Mayor Dianne Feinstein authorized the use of SFPD officers as “spies” to go into the bathhouses and monitor sexual activity with a particular eye open for unsafe sex practices (primarily condom-free anal sex). The spy controversy inspired significant advocacy, including an independent review of bathhouse safety procedures by local newspaper Coming Up! and a statement from the San Francisco Human Rights Commission condemning the closures. (Feinstein’s surveillance report was never made public.)

Of the thirty establishments monitored (which included bookstores and porn theatres), Dr. Mervyn Silverman, the City’s Public Health Director, said at an October 10, 1984 news conference that fourteen establishments ”have been inspected on a number of occasions and demonstrate a blatant disregard for the health of their patrons and of the community.” He ordered those fourteen closed. After some judicial wrangling, on November 28, a ruling functionally closed all venues operating as bathhouses. While the judge’s final decision never outright banned bathhouse venues, it instead prohibited the key feature of private rooms with locking doors and additionally added monitoring requirements for safe sex. The injunction specified that it was to remain in effect until the SFDPH Director “declare[s] the AIDS epidemic to be terminated.” This ruling held sway throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. As mentioned in the LGBTQ Policy Journal of May 22, 2021, “It is important to highlight that these venues were functionally closed as a result of judicial ruling. A heterosexual judge with no gay advisory committee determined what was an acceptable venue for men who have sex with men.”

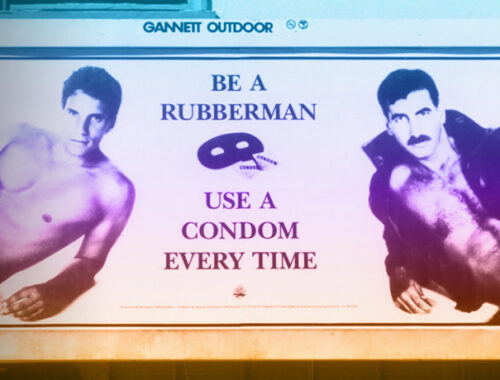

The argument put forth by patrons and others in the community was that, instead of closing the baths, they could be used to disseminate information about HIV and how to avoid acquiring it, to provide ample lighting and to take the doors off private rooms. Utilize the baths, don’t close them, the argument went. Unfortunately, to little avail.

Before the closings of the bathhouses, on March 27, at a meeting of the Harvey Milk Democratic Club, Larry Littlejohn introduced a municipal ballot initiative that aimed to close down the baths as a response to the raging AIDS epidemic. “Littlejohn’s ballot proposal galvanized the gay community in opposition,” renowned activist Cleve Jones told me. “That was the tipping point. We all reasonably feared an anti-gay vote, a slippery slope that could lead to who-knows-where? And so many of us felt it was better to leave it in Dr. Silverman’s hands.

“Personally, I was very ambivalent, torn on the issue,” Cleve continued. “I recognized that the baths presented a unique opportunity to spread the virus. But I wish we had kept them open to educate and test patrons, especially for closeted men going to baths and then back to their wives.”

Exactly what did the bathhouses provide for the community? Obviously, they were places where men could engage in anonymous sex. But they were much more than that. Some of the bathhouses offered a fully equipped gym for working out, swimming pools, steam rooms, saunas; some offered living room-like settings; some offered sodas and snacks for patrons. The sex was abundant, of course, but at the bathhouses, it was only one part of the draw of the baths.

Harry Breaux, activist and long-term HIV survivor, moved to San Francisco in the early 1970s. “A bathhouse where men are able to express their desires physically and engage in social interactions was a new experience for me,” Harry told me. “one I found myself participating in as though in a fantasy locker room. Many men all in towels or less. Often times the encounters were just that, encounters, but once in a while, in an hour or an evening, a connection would occur that would change me.

“The restaurant or snack bar and the living room areas were alive with interesting conversations about all sorts of ordinary things. These bathhouses were a place for networking before cell phones. In addition, there was a peace and basic kindness there with men all exposed as equals in their towels. No brand name shirts or plaid to identity who or what you are. We were equals. The baths were the golf games of the community. Many deals were made in those baths. The connections and the equality of the towel provided many career paths up and down. ”

Harry continued, “The height of my bathhouse daze in the ‘70s was visits from Oregon to San Francisco, ostensibly to buy ‘supplies’ but first, like cowboys finishing a drive, we needed renewal and baths. No better place than the assortment in San Francisco and other cities.

“Closing the baths in 1984 was like shutting off the internet today. Our lines of communication in the war on AIDS were severed here in this city. The solutions were in our faces and Dr. Silverman knew it (information, condoms, sanity), but Mayor Dianne Feinstein exercised her power from the basis of her fear, interests and prejudice. No other city I know of made such a devastatingly short-sighted mistake. AIDS awareness and prevention efforts lost out, but we lost more.” [I recently learned that New York City has also closed the bathhouses there.]

By the 1990s, some semblance of AIDS sanity began to prevail, and sex clubs such as Blow Buddies and Eros were permitted to operate, following the strictures that the community had proposed more than a decade earlier. Daralt, the former proprietor of A Taste of Leather: “In 1993 I partnered up with Ken Neal and started Mack/Folsom Prison on Folsom Street. We were different from bathhouses because we did not have the amenities found in bathhouses like private rooms with beds (or cots) and lockable doors, steam or sauna rooms, swimming pools, etc. Although we did offer some bunks to play on, there were no private areas to hide away and practice unsafe sex. Ours was a mostly stand-up sexual arena. I believe Mack operated in a ‘gray area’ of city laws and ordinances and was an open secret that we existed. The city health services frequently monitored activities at Mack and would report back to us of any observed infractions and also recognize our compliance with safety rules.”

With a concerted push by District 8 Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, in January of this year the City’s Health Department rescinded the restrictions that have kept the baths closed for decades. “It is symbolically significant right now,” Mandelman told the B.A.R. “Whether it is significant on the ground depends on whether entrepreneurs with the vision and financial capacities and the savvy to open can and operate one of these.”

“Hooray!!!” was Harry Breaux’s reaction to the lifting of the ban. “The personal social media device has isolated people. We touch less and are even dealing with a disease that argues against physical contact. Now HIV is, at least, controllable, allowing more gayness. It’s the capitalistic way. Supply and Demand. Expose Stigma. Allow willing, informed adults to play as they wish. BRING BACK THE BATHS!!!!!”

This reopening of the baths may signal that the city has learned that HIV is transmitted through behavior, not location. Maybe they’ve learned to trust that gay men at the baths have enough information, and self-esteem, to take care of themselves without Dianne Feinstein peering over their shoulders. Maybe the advent of PrEP has changed minds if not behaviors. Or maybe, as Harry said, it’s pure capitalism at work — those baths made a lot of money and paid a lot of taxes!

No matter. I think, though, that we can at least celebrate the fact that a time-honored staple of gay culture will be given new life in this fair city. It took overcoming nearly four decades of prejudice and faulty information, but we have prevailed.

Commemorating 40 years

Join us every month in 2022 as San Francisco AIDS Foundation marks 40 years of service to the community.

On this occasion, we take a look back and share our storied history of leadership in HIV prevention, education, advocacy, and care, and HIV history in San Francisco and the Bay Area since the beginning of the epidemic.

As we look back on our history, we approach the future with hope, and with a renewed sense of all that our passion and ingenuity can bring to enact positive change in our community. We will act in bold and brave ways to reach an end to the AIDS epidemic, and ensure that health justice is achieved for all of us living with or at risk for HIV.

After 40 years, we will not lose sight of our commitment to our community, and our vision for a brighter future.