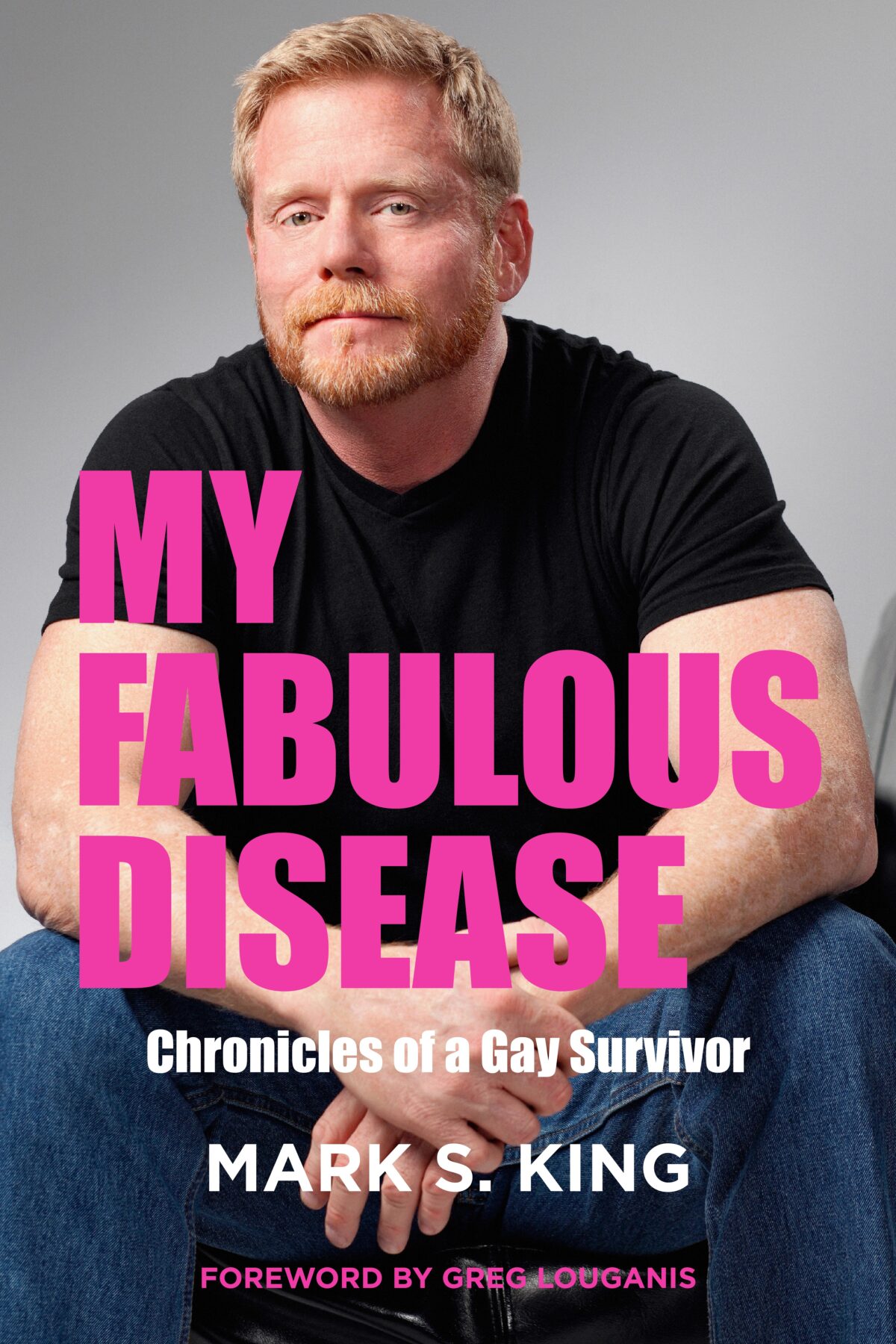

My Fabulous Disease: Chronicles of a Gay Survivor

Writing about Mark S. King’s work, Sean Strub, author of Body Counts, has said, “If the AIDS pandemic had a Mark Twain, it would be Mark S. King.” I see no reason to dispute that assessment.

Mark has been chronicling his life with HIV since he was first diagnosed in 1985. As a long-term survivor with nearly forty years of living with HIV, he has quite a lot to say. In addition to working at AIDS service organizations in Los Angeles, he began writing a column, “Marking Time,” syndicated in several gay newspapers. At the urging of his editor at www.TheBody.com, Mark turned his insightful attention to an online blog, “My Fabulous Disease,” which is read by thousands of LGBTQ+ folks who eagerly wait for his next blog entry to drop. His approach to the blog, he told me, is “to be emphatic, to be opinionated, and to tell the truth.”

That approach is quite evident in his new book, My Fabulous Disease: Chronicles of a Gay Survivor, an anthology of some of his favorite blog entries and some earlier pieces. The entries in the book form a kind of kaleidoscope of insights and emotions, ranging from hysterically funny to deeply contemplative, from joyful and celebratory to gut-wrenchingly somber. It is that range, along with his indefatigable sense of humor, that leapt off the pages for me as I read the book.

Mark’s writing is nothing if not provocative. For instance, just the title of his blog “My Fabulous Disease” kicked up a lot of dust in the beginning. Many readers, and some people who never read the blog but heard about the title, were irate — “There’s nothing fabulous about my disease!” “How dare you?,” they railed. But Mark is very savvy; he knows what he’s doing, purposely and humorously provoking such responses. After all, if your writing doesn’t provoke strong responses, what have you accomplished?

As one might expect from a book that brings together essays from nearly forty years of writing, the essays roam widely across the full spectrum of Mark’s life with HIV. He writes frankly about his early-in-life coming out (“Was I a Teenage Sexual Predator?”) and his “prodigious” sex life since (“My Sad and Trivial Night with Rock Hudson,” “Probing my Anal Phobia”). He bravely dissects his relationship with his family (“I Am the Man My Father Built,” “Hurting Mom on My First Gay Christmas”). He can scold his community (“Stop Bludgeoning Young Gay Men with Our AIDS Tragedy,” “The Inconvenience of Queer Activism”), or recount touching memories of our heroes (“Shopping at the Mall with Larry Kramer”), or celebrate the love we’ve made as we struggle along (“As Timothy Dies, a Great Love Endures,” “Once, When We Were Heroes”). He can fill your heart with sadness and your eyes with tears (“Suicide: A Love Story”) or leave you laughing your butt off (“The Fabulous Wizard of POZ”). Whatever response his writing produces in you, you won’t soon forget it.

The brevity of each of the entries in the book—as Mark told me, he likes to “get in, tell you a story, make my point, and say goodbye,” usually in 800 words or so—enables even the busiest reader to open up the book anywhere and read an entire entry in just a few minutes. And each entry, whether deeply sad or brightly comic, goes down like a delicious one-bite amuse bouche.

My Fabulous Disease will be published in paperback on September 1, 2023. One of the first stops on his book tour is San Francisco. His busy schedule here includes an on-air interview with Reggie Aqui on KGO-TV at 7:45 a.m. on Friday, September 15; a meet-and-greet at San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s Elizabeth Taylor 50-Plus Network weekly coffee meeting at Maxfield’s House of Caffeine (Dolores Street at 17th) from 10 am to noon on Saturday, September 16; and a community event at SFAF’s Strut (470 Castro St.) at 6:30 pm, where you can buy the book, and where Mark and members of San Francisco’s long-term survivor community will read excerpts from My Fabulous Disease to generate community discussions.

The following is a transcript of an interview I conducted with Mark on Thursday, August 3, 2023.

Interview with Mark S. King, August, 2023

Hank Trout: You were born in Alabama, right?

Mark S. King: Yes, I was.

HT: Tell me about your childhood.

MK: I’m the youngest of six kids, two of each, as we like to say — two girls, two boys, and two gays. I have a gay brother who’s about sixteen years older than me. I was an Air Force brat. My mom was pregnant with me when they moved to Alabama in 1960. It was the first time my mother ever said to my father, “Get a transfer! It’s 1960, it’s Alabama, get us the hell outta here.” She was from Michigan, so she was not used to the kind of racism and general politics of the South, so they left shortly thereafter. I was in Alabama for only a few months.

HT: Moving around as an Air Force brat, were you good at school?

MK: Traveling around like that was good for me, I think, because you had to make friends fast or else you felt disjointed. So I made friends fast. My childhood was good. My parents were married for almost sixty years before my father passed away. It was unremarkable, other than I had very influential parents. My mom was super-smart; my dad was a big entertainer. So I like to think that I got a little from both, but certainly more from my dad.

HT: When did you know you’re gay?

MK: In my early adolescence, as soon as I knew what attraction felt like. I was sexually active pretty early. I think that I was just looking for, not validation so much as “You are okay, this is okay, your desire is okay.” I wasn’t sure I was okay. I came out rather early because, once I figured out that central question “Am I okay?” I decided that if I’m okay, then it’s okay to tell people, it’s okay to be who I am. Which was a little outrageous because by that time we were living in Louisiana. I came of age in Bossier City wearing puka shells and jumpsuits and platform shoes. It was a lot to handle for my family and for my classmates. I was openly gay by the time I was a senior in high school. Were it not for the fact that my brother David was the campus jock football star, I probably would have been seriously injured by the bullies. He kept them at bay for me.

HT: I was wondering if you had been bullied for being gay as a child.

MK: I definitely was bullied early on. I was a “queer” and a “pansy.” I remember being kicked so hard in my shins on the playground that my legs would bleed and the blood would run down my leg and into my socks. I would go home, take off my bloody socks and throw them away discretely so my mom wouldn’t know I had been kicked so hard. I was trying to hide my shame of why it was that I was being beaten up.

HT: Years later, you moved to Los Angeles?

MK: I did. In 1981, I moved to L.A. I remember because I had been living in New Orleans, going to college where I could drink at the age of eighteen. And then when I moved to Los Angeles, I couldn’t drink because the [legal] age there was twenty-one. I lived in West Hollywood, so I had a couple of summers of love, as it were, before the lights dimmed.

HT: Tell me about Telerotic, the gay sex phone service you ran. Did you learn anything about gay men that helped you later in your AIDS work?

MK: Absolutely! Yes! It was fascinating anthropologically. I got this insight into what makes gay men tick sexually. It was $42 to talk to “the man of your dreams.” I would become different characters depending on what the customer had ordered. I made tens of thousands of calls over the years. When you are whispering into the phone and paying good money and there’s nobody else but you and the other voice, you tend to blurt out things. So I heard everything. It wasn’t simply the sexual mechanics of what gay men wanted; it was the vulnerability. Talking to men who were calling from small towns who had no other outlet, who were lonely, or wanted a boyfriend, or had just broken up with someone. There was a lot of humanity in those calls. I think it gave me a lot of empathy and insight into gay desire and everything that that means, internalized homophobia, a reticence to come to terms with what they really wanted.

So years later, as I began designing prevention strategies for gay men, having conversations about safer sex, I already had a really good idea of the profound power of sexuality and desire, and what gay men want and what they need to feel complete

HT: Do you think your dealing with gay men on that level contributed to your need to be of service in other ways?

MK: If AIDS had not existed, I would have taken that education I received through Telerotic and just tucked it away as an interesting experience. What drove me to service was AIDS. I was diagnosed in 1985 as soon as the test came out, and then we had a choice to make, all of us: “What do I do? How do I survive this? Can I survive this?” A lot of people retreated into themselves, and that’s solid, I don’t judge that at all. But there were those of us who said, “Goddamn it, I’ve gotta DO something! Where do I go? How do I help?” Some of that might have been some sort of cosmic bargain — “I’ll do something nice and maybe I’ll live another day.” For me, I was immediately drawn to those doing the work of HIV.

I went to work at age twenty-four for the first AIDS organization founded in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation. We helped people die with dignity. I met gay men, largely, but also heterosexual men and women, Black men and women, with whom I had never worked in my young life. So I had a lot to learn about feminism and systemic racism. I thrust myself into this world of mortality and compassion and death and dying and racism. It was quite an education. I felt like I did not have any other choice but to be of service.

HT: Years later, in 1996, you started this program called Reconstruction for guys who had been at death’s door but suddenly were healthy again thanks to the cocktail.

MK: It was 1996 so we were coming out the other side of the pandemic, medically speaking. But we hadn’t come out the other side emotionally, psychically. I was working at AID Atlanta at the time. When people started living again, the Lazarus Effect as it was called, I realized that maybe I had not just two years, but ten years, twenty years, forty years ahead of me. It’s funny, I had prepared myself emotionally to die, and then I felt guilty that I didn’t feel grateful for those added years. I realized, “Oh my God, we have a lot of work to do to recalibrate.” I had been living in two-year increments my entire adult life, waiting for the spots or the cough. When the cocktail came along, I was angry in a strange way. I felt emotional whiplash — “you/re gonna die, you’re gonna live, you’re gonna die, you’re gonna live.” I had psychically prepared to live a very short life. I knew that if I was feeling those things, so was everybody else. So we held a town hall forum in Atlanta about the practical and emotional concerns of renewed health. The town hall was packed, and these folks had a lot to say. “What am I supposed to do? Do I go back to work? How will I explain a five-year gap in my resume? I’ve spent all my money, I took the trip around the world, I maxed out my credit cards, I prepared myself to die — what the hell am I supposed to do now?”

Reconstruction was a six-week series of lectures addressing mental health, financial planning, back to work issues, social considerations, and more. And it turned out to be a good idea! Reconstruction was replicated in ten cities throughout the country. It was an amazing time. I’m really proud of that.

HT: Your biography online says that you started writing in 1985 when you were diagnosed. Had you done any writing or publishing before that?

MK: I had been writing as a columnist in gay newspapers. In some of the papers, my column was called “Marking Time.” I appeared in the Washington Blade, the Windy City Times, the L.A. Frontiers, and other newspapers. As a writer, I like to get in and out in about 800 words. I like to get in, tell you a story, make my point, and say goodbye. Some of that early work is in the book reaching back to the Nineties, at least.

I developed a “voice,” my voice as a writer: to be emphatic, to be opinionated, and to tell the truth. I learned a long time ago that there is nothing wrong with revealing your faults, your mistakes, or your ignorance, especially my ignorance when it came to things like race and gender and gender identity. I’ve gotten a lot of goodwill from my readers because they know I’m doing my best and I want very much to understand things that I may be ignorant about.

HT: When did you start blogging?

MK: Bonnie Goldman, the founder of the website TheBody.com, one of the most comprehensive sites about HIV and AIDS, had published some of my things. She said to me, “Why don’t you blog for us?” And I said, “What’s a blog?” She gave me very good advice. She said, “Mark, the more you reveal, the more you draw people in. Don’t be afraid to be honest, don’t be afraid to say the wrong thing or admit your ignorance; it’s okay. The more you reveal, the more you bring people in.” She has since passed away, but that was probably the most influential advice I ever got. My column became “My Fabulous Disease” once I started blogging for them.

The through-line of my work has always been my sense of humor. You’ll see it in my book and in my blog. That’s just how I’m built. Humor is my shield, my coping mechanism, and it’s very much who I am. I’m very likely to laugh at my own misfortunes, but I’m very careful not to laugh at anybody else’s. I’m respectful of this disease and this community. But HIV is not going to steal my joy anymore, not for one more fucking minute. I think that is evident in my work.

HT: I love the title of your blog — when I first read “My Fabulous Disease,” I thought, all right, this is for me, I gotta read this!

MK: Y’know, it’s meant to be cheeky and provocative. I certainly have heard from plenty of people over the years — “Well, my disease isn’t so goddamn fabulous! How dare you?” And I get it. But it’s meant to be provocative but it’s also, again, just the way I’m built. That’s how I approach things.

HT: I want to talk about specific pieces in your book. What criteria did you use in selecting one story over another?

MK: It’s really simple. I just wanted my best work in there. I included the work that makes me feel the proudest as a writer. It took me years and years to call myself a writer. I would say to people, “Oh, I just kind of tell these stories,” and be dismissive of my own work. And I know now that I am a writer. That is who I am first and foremost. I wanted to select those pieces that would take the reader on a journey, that would have a strong point of view and were fun to read.

There are a lot of types of things that I did not use. I’m not a breaking-news kind of guy. My pieces are a little more thoughtful after the fact; I want to think about things and then write more contemplative pieces. So I took out a lot of opinion pieces that were about the politics of HIV and organizations and behind-the-scenes pieces.

My blog is my labor of love, my contribution to our community dialogue. It’s my platform to say what I want. I don’t work for an organization, I don’t work for the government, I don’t work for big pharma, so I can say anything I fucking want to say about anybody — and I have.

HT: The pieces in the book range from hysterically funny to very somber. I’m sure some of your pieces have stirred up quite a hornet’s nest of controversy. I’m thinking now of “Stop Bludgeoning Young Gay Men with Our AIDS Tragedy.” What kind of response did that blog piece get?

MK: It got ferocious response, ferociously angry. It’s funny because as a long-term survivor, Hank, you fit the profile of the people who hated that piece. They couldn’t seem to separate having respect for our history, protecting and upholding our history, and using it as a blunt instrument to somehow punish younger gay men because they didn’t go through what we went through. Well, thank God that they didn’t go through what we went through! The piece is very strong, but I think that it acknowledges the importance of our history. It just says, let’s not shame or point fingers at younger people just because they haven’t had the same life experiences that we’ve had.

HT: The most gut-wrenching and arguably the best written piece in the book is “Suicide: A Love Story.” Why did you decide to include that piece?

MK: I included it because it is the truth and it is incredibly intimate. The story is of my brother and his lover of thirteen years, who were my role models. They were the fist successful, loving marriage of two men that I had the honor of witnessing. The story recounts his revealing to me the circumstances of the night his beloved partner passed away. It gives you that story from two perspectives. The first is my having been there just after he passed and having to witness the wreckage, my brother’s emotional wreckage, having to deal with his lover’s passing. The second is, months later, his telling me the actual story of what happened and what they had to go through that night, when he — at his lover’s demand — helped him pass away. It is gut-wrenching, but it’s not an uncommon story. It happened all the time. I’ve had a few friends call to say goodbye the day before they passed away by ending their life on their own terms.

HT: One of the most haunting images in that piece is not seeing but hearing the wheels of the gurney as he’s being wheeled out of the apartment. It’s an incredible image.

MK: Thank you. My brother had called the coroner and he had told me to go sit in another room because he didn’t want me to see his partner. But I could hear them removing his partner, the wheels rolling across their Spanish tiled floors and the gurney clicking on the steps down the way to the vehicle. That was rough.

HT: One of the other pieces, “The Inconvenience of Queer Activism,” about the #NoJusticeNoPride disruption of the Pride Parade in Washington DC caused a lot of response too. [The #NoJusticeNoPride contingent blocked the DC Pride Parade for about an hour, causing much consternation.]

MK: It did. It’s funny because that is the kind of piece that I did not include elsewhere in the book. It’s based on a particular event that happened. But this one, I couldn’t resist because it represents part of my own awakening as a someone who isn’t concerned with just the social justice of other white gay men. It’s about being expansive. Life is about addition, not subtraction, and that’s why I included it in the book.

HT: Reflecting on #NoJusticeNoPride, what do you think about the state of today’s queer activism? What are we doing right? What are we doing wrong?

MK: First of all, we’re not in charge anymore, Hank. As it turns out, there are a couple of generations after us who seem to be in charge. And good for them!

I think what we’re getting right is our embrace of gender identity and all the permutations of sexuality and gender. That alone has been an education for me over the last ten years. I think that we are getting right our support for those whose gender expression is different from ours and maybe something new. I think that the future is Black and female. That is clear from some of the most exciting activism going on in the scene right now, which is led by groups like the Positive Women’s Network. And if you look at the leadership of other influential HIV political groups, you will find Black women at the helm, or at least in positions of leadership. I am thrilled to see that!

I think what we get wrong is that a lot of gay white men got what we came for and left the playing field. A lot of gay white men are happily gay-married and living in the burbs with their adopted kids — and that’s great for them But we have left behind others who need our help. We have to remember who was at our side when we were struggling and who were asking to be noticed and recognized and assisted. For most of my adult life, I saw people in leadership roles who looked like me. And I got used to that. So I have to recalibrate to have sensitivity and understanding and be teachable so that I can be an effective ally to people who do not look like me.

HT: I know a lot of people who are excited to meet you on your book tour visit to San Francisco.

MK: I’ll tell you what I’m excited about. I’m a community guy. In San Francisco, we have invited community members to come read excerpts from the book and talk about their own experience. That experience may be very different from mine, and that’s great! When you have a person of color or a woman reading an excerpt from my book, and then saying, “That’s not my experience and this is why,” I have to claim my own privilege and remember that there is a reason why someone like me is a long-term survivor of nearly forty years. It has everything to do with gender and race and privilege and resources. I am not flip about that at all — I’m flip about a lot of things, but not that. That means that in San Francisco and other cities, we’re going to have a very interesting conversation that will provide wisdom and insight far beyond what my book alone can provide. The book can be a springboard for other people to bring in their expertise and their point of view. To me, that’s a win, that’s fantastic.

HT: One more thing before we go. The last piece in the book, “The Odds of Love,” about you and your husband Michael, is just delightful, full of hope and enthusiasm and a sense of wonder. Why did you make this the last piece in the book?

MK: I wanted a soft landing for my readers, and I wanted something that was hopeful and described my life today. It asks, what are the odds of our surviving at all, the odds of our being in love again. At our age, the odds aren’t great. And yet I’m lucky enough to have done that. And I hope the readers are happy for me.

My Fabulous Disease: Book Reading & Discussion

Join us for a special community event in commemoration of HIV & Aging Awareness Day! We’re hosting GLAAD Award-winning author Mark S. King and special guests for readings and discussion of Mark’s new book of essay as a 40-year HIV survivor.

Saturday, September 16, 6:30 pm

Strut, 470 Castro St., San Francisco