Legendary Marlon Riggs speaks to the modern-day Black gay experience

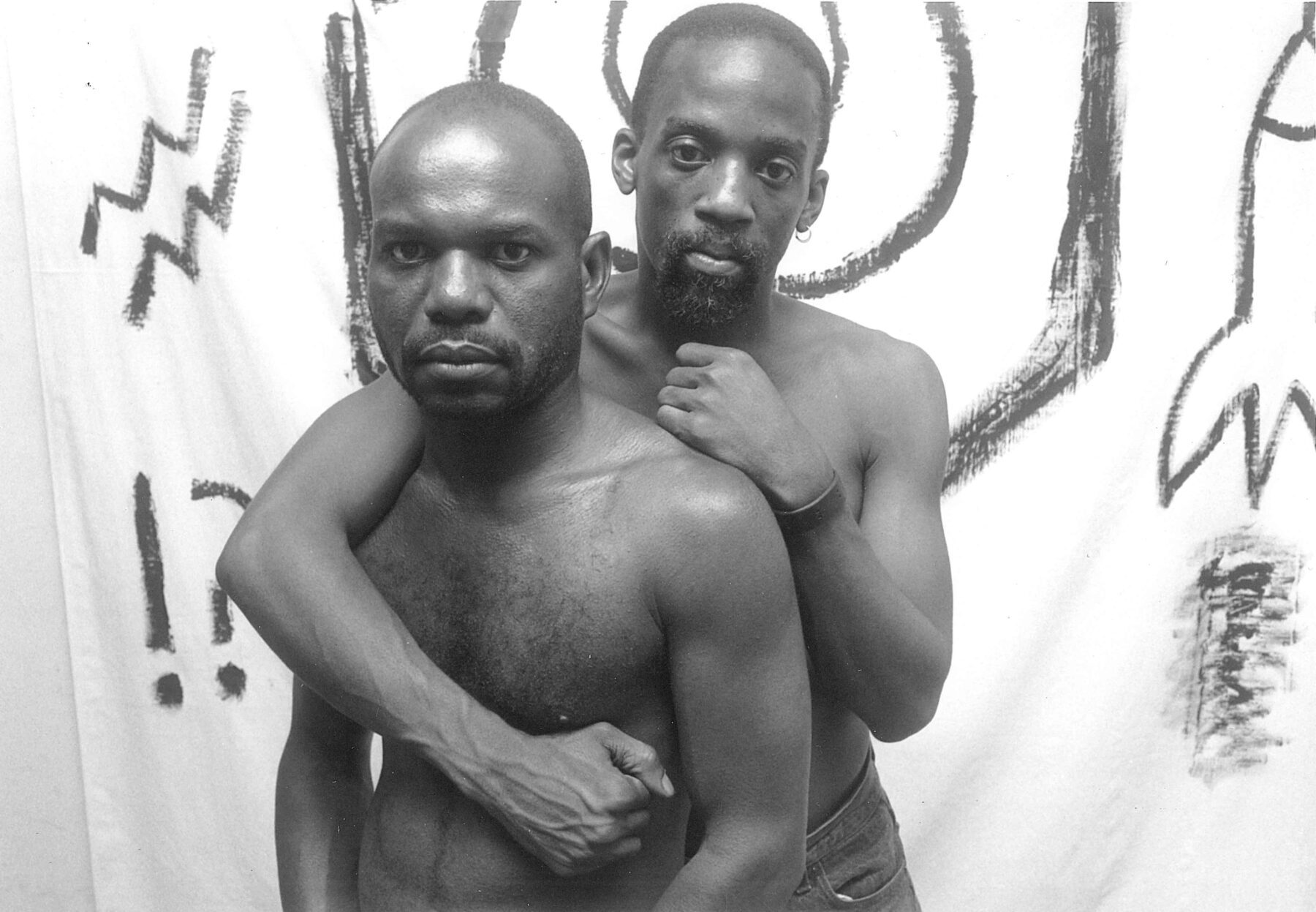

Marlon Riggs lit up the world of documentary film with his brilliant, vivid prose, and fervrous gay rights activism–a visionary who used his camera to shed light on the experiences of those often left in the shadows. As a Black, gay man, he was not afraid to explore the complexities of race, sexuality, and HIV and AIDS–and he did so with a bold, unapologetic voice. Although Riggs died from complications of AIDS in the mid-1990s, to Black gay men like me, his work speaks volumes to experiences that resonate even today.

Born in the heart of Texas in 1957, Riggs grew up with conservative, working-class roots, but his spirit yearned for more. He journeyed to Stanford University, where he studied the art of film and the power of communication, and soon after, he chased his unyielding dreams for artistic expression in New York.

His masterpiece, “Tongues Untied,” released in the year 1989, remains a testament to his courage and his talent. Through a tapestry of poetry, music, and personal tales, “Tongues Untied,” explores many things–HIV and AIDS, a Black and gay identity, and the complexities and contradictions of life in San Francisco’s predominantly white and gay community, the Castro.

The tantalizing lure of the Castro had been a significant reason I moved to the Bay Area five years ago. I remember walking the narrow streets and feeling the buildings–steeped in LGBTQ history–almost hugging me as I wandered. I remember hearing laughter and music all around me. After a few months of living in the Bay Area, I began to realize the neighborhood’s deep-seated history of exclusion.

Today, the gentrification of the Castro has contributed to the displacement of long-time residents, including Black and gay men, who can no longer afford to live in the neighborhood. When I looked at the prices of rooms for rent in the Castro, I realized that I could have my own place in other parts of the city for the same price. Black gay men may also feel unsafe in the Castro due to incidents of racial profiling and police harassment in recent years. “Do I want to sign up to be the next person barred entry because I wanted to wear cornrows?” I asked myself.

“Oakland’s where it’s at,” people of color would advise. When I interviewed Mellanique “Black” Robicheaux after having been named one of San Francisco Pride’s “Grand Marshals,” she discussed challenges working with Castro bars when she was invited to DJ. “They wanted people who would play music that they were used to,” she recalled. That, and other microaggressions, are what led her to venture outside of the Castro scene.

Riggs’ interviews with Black gay residents of the Castro in 1989 revealed the dualities of existence in this neighborhood. On one hand, the Castro offers the promise of a haven of community and acceptance for Black gay men who often face rejection elsewhere for their sexuality. On the other hand, the neighborhood fails to deliver and can often feel like a hostile place, where those same men’s Blackness may be tokenized and even exploited in a culture that exalts and prioritizes white, gay identity.

Strikingly, the reality of the Castro that Riggs exposed more than three decades ago has only slightly shifted today. Holding space for both of these realities makes the Castro feel both tantalizing and terrifying at times for Black people like me.

“Tongues Untied” also featured one of my favorite poets, Essex Hemphill. It was Marlon Riggs who found a way to capture Essex Hemphill’s powerful storytelling on film. Essex once said, “We must affirm the lives of all black people, including black gay men, in our struggle for freedom and justice,” and Marlon Riggs and he were incredibly aligned on this point and it kneaded into their artistic collaborations. “Black is… Black Ain’t,” (1994) a critically acclaimed documentary that examines the meaning of Black identity in America, was another collaboration.

With passion and purpose, Marlon Riggs used his platform to raise awareness about the AIDS epidemic and to fight for LGBTQ rights. Marlon Riggs gave us “Color Adjustment” (1991), a film that explores the representation of African Americans on television, and “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (No Regret)” (1992), a short film that explores the complexities of black gay desire and love, and others.

When I told Andrè Bloodstone Singleton, a Black, queer historian and artist in the Bay Area that I wanted to shine a light on Marlon Riggs’ work, he beamed with excitement. “Marlon’s work never received the attention that it should have. Many film festivals said his work was either ‘too Black’ or ‘too gay.’ My art isn’t made to be well received, either,” they added. “It’s about moving our society slowly to where it needs to go.”

One of the things I think we have deeply undervalued in our society is the power of storytelling. We must tell our stories in their unabashed fullness, they must be welcomed with open hearts, and they must be shared to the greater society. That’s how we secure civil rights. In fact, no battle for civil rights has ever been won without documentation.

Marlon Riggs understood the power of storytelling, and he used his films, writing, and speeches to connect people across lines of race, sexuality, and culture. Although he died from complications of HIV/AIDS in 1994, he still calls upon us to work towards creating inclusive and supportive environments for all, with the power of his words ringing out long after his films end.