Although Pride month is behind us, the memory of rainbow flags waving in the summer breeze still lingers. No matter the time of year, their proud representation has the ability to transport me back to my first Pride celebration in Athens, Georgia back in 2014, which was not only a celebration, but also a stark reminder of how much more work we must do collectively as a society to make the world a safer place for queer people.

For instance, it was there at the Athens Pride Parade, among a sea of color and joy, that hateful rhetoric attempted to draw a direct dotted line between being gay and AIDS. Signs that read “GAY = Got Aids Yet?” clung onto my memory, but their inflammatory words, intended to diminish us, only served to make my voice louder, my identity prouder, and my commitment to advocacy stronger.

Not only was their hateful rhetoric cruel—it was also increasingly outdated. While the disease first took storm within the gay male community, and significant strides have been made to end transmission, we can’t rest on our laurels. The virus continues to significantly impact some communities disproportionately.

In the UK, for the first time in a decade, heterosexual individuals have surpassed gay and bisexual men in new HIV diagnoses. The figures from the UK Health Security Agency paint a different picture from the one I’ve seen Pride protestors trying to brand into the public consciousness: 49% of new HIV diagnoses in 2020 were among heterosexuals, compared to 45% in gay and bisexual men. What’s more, these statistics unveil a troubling trend: heterosexual individuals, particularly women and those over 65, are more likely to be diagnosed at a late stage of HIV, when the virus has already begun to damage the immune system within the UK.

This is a stark reminder of the need for expanded awareness and testing across all demographics, challenging the dangerous assumption that HIV is not a concern for heterosexual people. As Kate Folkard, Interim Deputy Director of the HIV Division at the UK Health Security Agency, states, “We must address inequalities and find creative ways to achieve a reduction in transmission across all populations.”

And naturally, one might wonder, if this HIV diagnosis trend among straight people can happen in the UK, may the US one day experience similar HIV trends?

In the US, where the CDC’s initiative to end the HIV epidemic aims to lower new cases by significant margins in the coming years, the strategy includes increasing HIV testing, improving access to care, and promoting preventative measures like PrEP with campaigns that target both straight and queer communities.

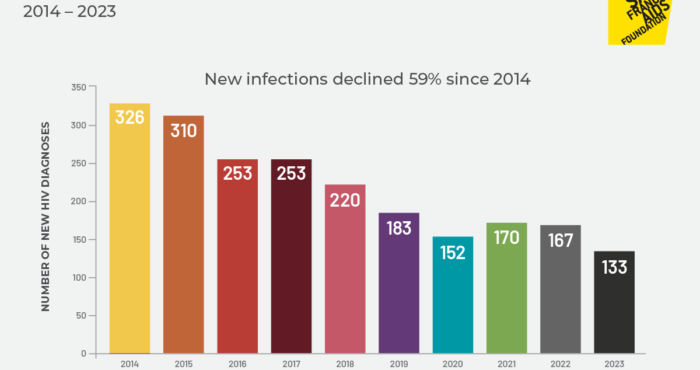

And thankfully, it’s true that the number of overall HIV infections has been in a steady decline. Yet, despite these efforts, again, disparities persist. In the US, 22% of new HIV diagnoses in 2021 were from heterosexual contact, and seems to be a proportion that’s on the rise similar to the UK, but a disproportionate 69% of new cases still occur in men who are gay, bisexual, or have sex with men in the US.

So, while in the US, unlike the UK, queer people continue to make up the largest cohort of new diagnoses, we must also consider the data that tells us quite clearly how not all queer communities have the same relationship with HIV transmission and prevention.

Black and Latinx communities, for instance, are particularly affected, making up more than half (70%) of estimated new HIV infections, despite representing a smaller percentage of the overall US population. In 2022, approximately 44.5% of clients self-identified as Black/African American, 25.8% as White, 25.3% as Hispanic/Latino.

Consider how African American and young people, though highly at risk, are under-prescribed PrEP due to structural and societal barriers, and there’s a gap in continued usage among Black and Latinx young adults, and those who use substances due to financial concerns, lack of awareness, and cultural attitudes.

Our efforts to end HIV transmission must adapt to address all communities impacted, including straight people and communities of color. We can no longer paint broad strokes that target just the gay community, but we must instead ensure inclusive access to prevention, education, and care for all at risk, regardless of whether someone is gay or straight, while also remembering how race and identity may also impact transmission risk.

The battle against the virus is as much about combating the stigma and ignorance and injustice that still exists in society as it is about promoting scientific advancement and healthcare equity. Let us remember that our advocacy must be as inclusive as it is passionate, reaching every corner of our diverse society.