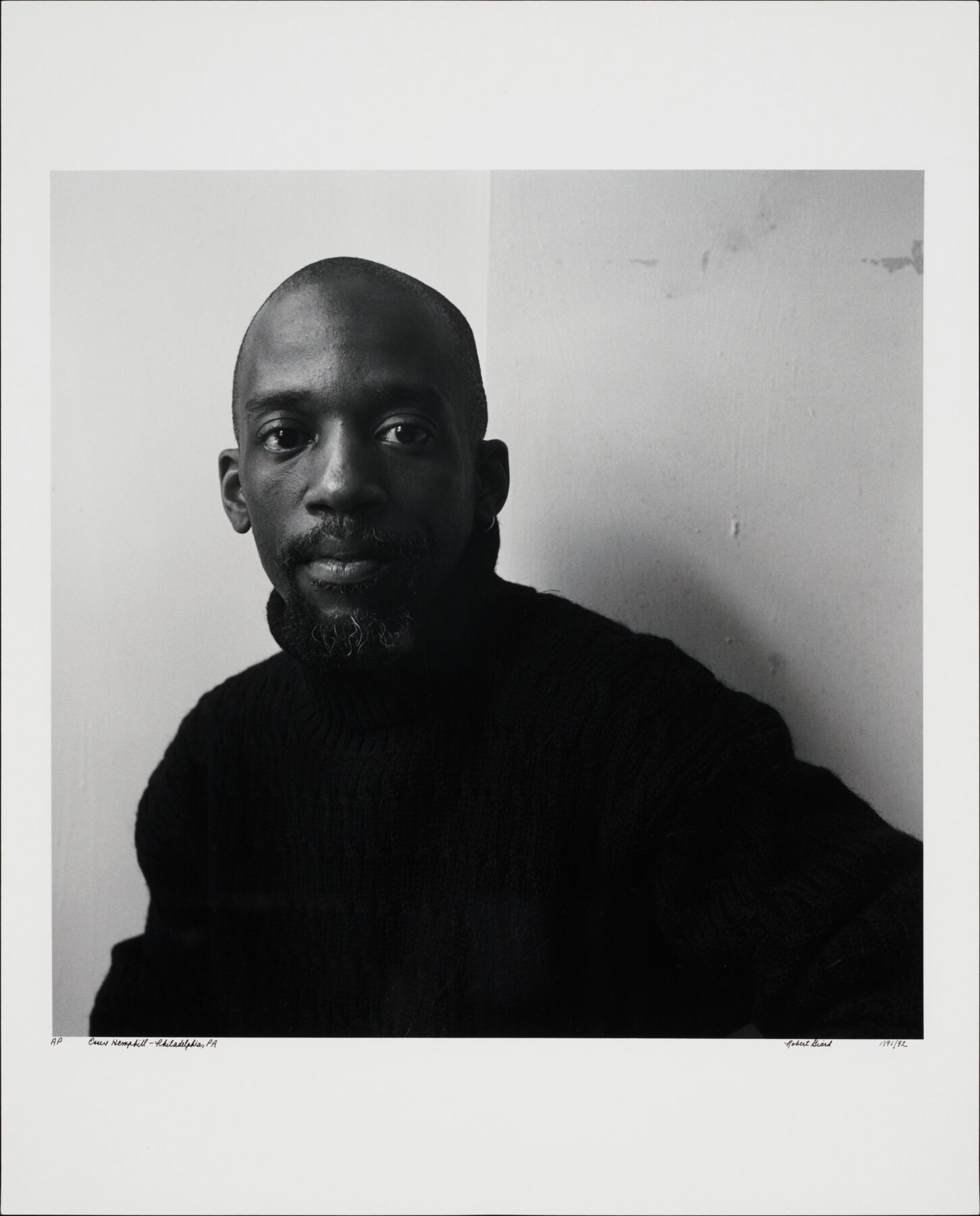

Essex Hemphill: A Bold Voice in the Struggle for Black Queer Liberation

Essex Hemphill left an indelible mark on the fight against HIV and AIDS as a visionary literary artist and activist.

A potent blend of honesty, political and social critique, and celebratory spirit, his writing fed a generation fighting for justice and equality. Only recently, I found myself combing through his verses and yard-length prose, enveloped by his edgy, yet provoking ideas, and wondering why it had taken so long for me to discover this treasure.

Each Black History Month, Martin Luther King, Jr, Rosa Parks, and Jackie Robinson always hung high on the syllabus. For decades, these cherry-picked stories remained palatable for the white gaze, I later learned in adulthood. They’ve been condensed into easy-to-understand, easy-to-adopt values that could be contorted and misrepresented as not too threatening, and not too oppositional to larger institutional systems.

If I really want to explore variety in the Black human experience, and be challenged beyond what fits into mainstream boxes, I also had to search for the untold stories. The rebels, the overlooked, the ones who caused a stir — those are the ancestors I want to learn about next. Show me the nonconformists, the invisibles fighting to be visible, those who didn’t wait for a platform but built one for themselves.

Born in Washington D.C. in 1957, that’s Essex Hemphill.

Hemphill masterfully reimagines heaven in his poem, “The Tomb of Sorrow.” Technically the Bible doesn’t give readers a clear description of what heaven looks like. Anything much beyond Revelation’s 21:12-13’s description of “a great, high wall” with “twelve gates and with twelve angels,” falls into the eyes of the beholder. So, what does Hemphill do? He places tall, hunky “Black Drag Queens” as heaven’s guardians.

Sequins crested into their glorious fabrics cast a blinding shimmer as he greets each queen with a deep kiss. For all of the Black, gay boys like me, we don’t have to accept that heaven wasn’t for us. Despite conservative expectations, we hadn’t gone the other way down Revelation’s so-called “broad road” which “leads to destruction” and through which “many enter.” In fact, Hemphill’s dethroning of the normative white god, reminds us that the Bible never said heaven’s “narrow entrance” excluded Black “faggots.”

As a captivating performer, Hemphill brought his words to life through his readings and shows. He once proclaimed, “I am a vessel through which the spirit flows,” and his spirit was on full display in his performances. Hemphill’s humor and wit infused his shows, and his passion and commitment to justice shone through in every word. And with characters as wild but perfectly affirming as “Black Drag Queens,” you can imagine how his work continues to inspire and move others to this day.

Hemphill also starred in several documentaries, including “Black Nations/Queer Nations” (1995). In this experimental documentary, he appeared as an advocate for LGBTQ rights, highlighting the intersection of race and sexuality. In the film “Black Is…Black Ain’t” (1995), Hemphill explores the complexities of black gay identity and the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality. In “How to Survive a Plague” (2012), Hemphill is remembered as a fearless activist who used his voice to fight for the rights of people living with HIV and AIDS.

Hemphill’s death from complications of HIV came on November 4, 1995. That same year 26 million people had been affected with the virus, and remained on the rise, especially in the Black, gay community. Still, the Black, gay community faces an unbalanced threat of the virus. According to the CDC, Black gay and bisexual men accounted for 26% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2018, despite being just 2% of the population.

Up until his final hours, Hemphill’s activism burned brightly, and his voice called for greater awareness and action in the fight against HIV and AIDS. He wrote extensively about the impact of the disease on the LGBTQ community and the need for support and action. He criticized the lack of attention and resources given to the epidemic and called for change.

Hemphill’s work helped to break down the walls of shame and stigma associated with HIV and AIDS, particularly in the Black, gay community. His activism and writing had a profound impact and continues to inspire and empower those living with the disease as well as those who can make connections to a larger, universal human experience. Let his story serve as an example of our collective Black History – history which has indelibly always been queer.