Ending the Epidemics: Conversation in California’s East Bay

Community members, community organizations, and health department officials from Oakland and the San Francisco East Bay gathered at a town hall in November to support the End the Epidemics campaign in California and discuss how it would make a difference for local efforts to address HIV, hepatitis C and STIs.

With more than 5,000 new HIV diagnoses happening every year in California, and increasing rates of hepatitis C, chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis, the End the Epidemics Coalition urges California’s Governor and legislators to develop a state-wide plan to address these interconnected epidemics. The campaign also calls for increased state funding for HIV, STI and hepatitis C programs in California.

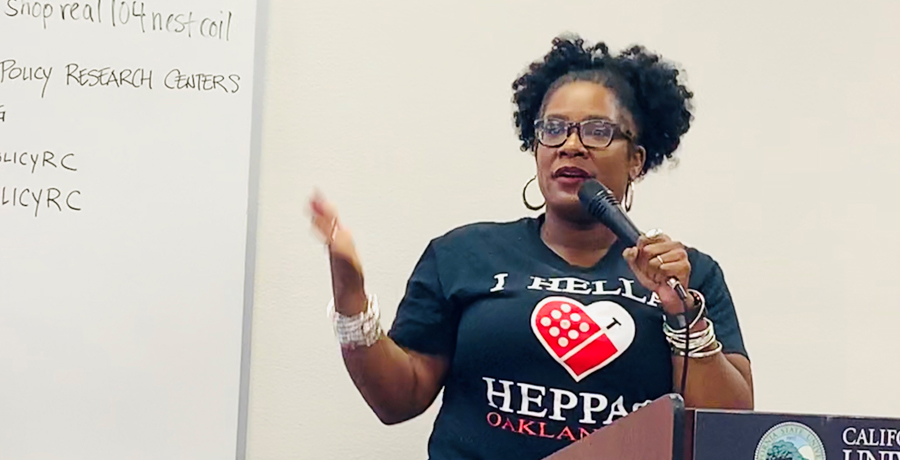

“The reality is there’s no way that we’re going to get to the end if we don’t work together,” said Demisha Burns, from WORLD, who opened the town hall. “There’s no way that we’re going to get to the end if we don’t speak out. And realize that it’s not me, it’s not you, it’s going to be a collective effort.”

Connecting HIV, STIs and hepatitis C in a statewide plan

The town hall speakers emphasized the interconnectedness of HIV, hepatitis C and STIs, and highlighted the need for these epidemics to be addressed as one syndemic instead of separately.

“We have the biomedical tools to end these epidemics. What we have not been investing in is actually looking at this as a syndemic, which also addresses the social inequities that drive health inequities. HIV, HCV and STDs disproportionately impact the same more vulnerable communities,” said Anne Donnelly, from San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

“Having an STD increases the likelihood of acquiring HIV. Among people who are living with HCV and HIV, HCV progresses faster and more than triples the risk for liver disease, liver failure and liver-related death,” said Erica Pan, MD, MPH, FAAP, the interim director at Alameda County Public Health Department. “These need to be treated together and in conjunction with approaches that address health inequities and the social determinants of health that magnify these epidemics in our most vulnerable populations.”

Part of the reason the End the Epidemics campaign is calling for a state-wide plan is because we know that state-wide plans are effective, said Donnelly.

“In 2014, New York put together a task force to end HIV—they had the political will, and the governor endorsed [the statewide plan]. New York has seen close to a 30% drop in new HIV infections, compared to California where we basically have seen no drop,” said Donnelly. “The New York plan has been so successful that they are starting a hepatitis C elimination plan as well.”

“We need a statewide approach with a plan and specific goals. It will be the most effective if this is statewide because we all know that diseases do not pay attention to jurisdictional boundaries, nor do systems of care,” said Dr. Pan. “We all need to do more to work together to engage key community partners, and bridge across all the siloed aspects of health and wellness that exist now. Traditional and uncoordinated approaches to each disease, and across public health, medical providers, mental health providers, health care systems including insurers, and social services all need to collaborate to develop a true continuum of prevention and care.”

So far, more than 150 organizations across the state have signed on to the End the Epidemics community consensus statement. Community leaders are hopeful that the campaign will bring much-needed funding to organizations across the state.

“Over $30 million were cut from HIV prevention programs during the recession in 2009—only 12 million have been restored since then. It’s been 10 years,” said Sylvia Castillo from Essential Access Health.

There has also been limited state funding for HCV testing and linkage to care, and STI prevention and treatment.

“Before securing $5 million last year for HCV funding, the [state] HCV program was running on less than $200,000 of ongoing money per year,” said Donnelly.

The state of the epidemics

HIV infections remain stable year-after-year across California and in the East Bay, while the number of hepatitis C and sexually transmitted infection (STI) cases continue to grow.

“More than 5,000 Californians were diagnosed with HIV last year, more than any other state in the nation,” said Burns. “More than 400,000 California residents are currently living with HCV [hepatitis C]. STD cases reached a record high for a third year, with more Californians being diagnosed with gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis in 2017 than before.”

In Alameda County, which includes Oakland, about 200 HIV diagnoses were reported in the previous two years, shared Dr. Pan. African Americans had diagnoses rates that were five times higher than among whites, and rates among Latinx community members were twice as high as whites.

“In Alameda County, we estimate that we anywhere from 900 – 1,100 cases of chronic hep C every year based on 2011 – 2015 data,” said Dr. Pan. “California also has the highest reported number of STDs in the country, and we’ve seen dramatic increases over the last several years – to the tune of over 200% increase in syphilis and gonorrhea compared to 10 years ago. We’re also seeing similar increases here in Alameda County.”

Voices from community members and community organizations

“I’m [involved] because I’m part of the community,” said Terri Haggins, a community member and HIV activist who attended the meeting. “When you talk about including everybody and having a coalition—don’t forget about us. You have clients who can do some of the same work that you’re doing. That would be willing to do some of the same work that you’re doing. I can go and talk to a woman that has children, who is worried about ‘Am I going to live?’ because I became positive in the 90s when [HIV] was a death sentence.”

One of the key challenges in responding to the HIV epidemic is reaching young people—especially young people of color, said Dran Summons, who is chair of the AIDS Project of the East Bay youth advisory board.

“I ask myself, ‘How can I take advantage of my youth, to reach people to look like me, are the same age as me, are in similar communities as me, or who think like me?,’ said Summons.

Cori Moreland, a health navigator for AIDS Project of the East Bay, spoke about the changing nature of the epidemic in the East Bay, and how outreach workers are responding.

“The majority of Black people now—due to gentrification and other things—are homeless,” said Moreland.

Where once the focus was on reaching gay and queer community members with testing services in bars and clubs, Morland said now the focus has shifted to prioritize people in homeless encampments.

“We are holistically helping people—giving access to resources for getting an ID, giving people ponchos, blankets, sandwiches, things like that, so that people understand we’re all community. We’re here to make people feel like they are real people. That’s how our testing and linkage has changed as a whole.”

“We have 8,000 people at any given time living on the streets in Alameda County, and it’s only increasing,” said Sophy Wong, MD, from East Bay Getting to Zero. “We have a ton of work to do. I hope this encourages us to really move forward, and keep reaching people and doing stronger street outreach for the folks living in tent cities.”

Loris Mattox, executive director of the HIV Education and Prevention Project, spoke about their organization’s continuum of harm reduction care for people who use drugs, many who are experiencing homelessness.

Engaging people at the lowest threshold means offering a drop-in space for people to get food, wash their clothes, shower and just sit for a while.

“We literally just make a connection. That’s the bottom line of what we’re trying to do. We want to establish a relationship with the people we serve,” said Mattox.

Further along the continuum, said Mattox, are syringe access services to reduce the spread of HIV, hepatitis C and other infections. To prevent overdose, the team distributes and trains people on how to use Narcan, an overdose prevention drug. They also provide access to medication assisted treatment services to people interested in reducing or stopping their substance use.

“We go from basic need, from reducing drug-related harm, to preventing death and reducing drug use,” said Mattox.

Structural determinants of health—including poverty, stigma, racism and discrimination were discussed by many attendees as significant barriers to their work to end these epidemics.

“These issues are all widening gaps and are visibly illustrated in our current magnified homelessness crisis in California,” said Dr. Pan. “HIV, HCV and STDs are driven by similar social and economic conditions and disproportionately impact many of California’s most disadvantaged communities, including Black and Latinx communities, gay and bisexual men, transgender individuals, women, youth and people who use drugs.”

“It’s nice to say that funding would be used to strengthen existing services,” said Mattox. “But when those services are rooted in structural issues like racism, discrimination and stigma—those services are going to be kind of rocky. What would make it most effective, is if we stop thinking about trying to catch leaks and patching leaks, and focus on the structure and foundation.”

Activism to change laws and policies in order to prevent discrimination against Black people in health care is a critically important way to confront racism in health care, said Mattox.

“Advocate for system change, not just resources. This takes a long time. But you have to remember that systems change is an invested effort,” said Mattox.

Sign the petition to End the Epidemics

We are at a pivotal moment in the HIV, hepatitis C and sexually transmitted infection epidemics. Sign the petition to demand a plan to end these epidemics in California.