It’s an exciting time in the world of HIV treatment and prevention with the development and testing of long-acting medications. Injectable medication, administered every one or two months, may soon change the landscape of antiretroviral therapy–eliminating a need for people living with or at risk for HIV to take daily medication. The U.S. FDA has already approved Cabenuva (extended-release cabotegravir and rilpivirine), a once-monthly injection for HIV treatment, and approval for long-acting cabotegravir for PrEP may not be too far in the future.

Research presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2021 by Raphael Landovitz, MD, brought to light questions about effectiveness and drug-resistant infections with long-acting cabotegravir used for PrEP.

What should people who might consider taking injectable cabotegravir for PrEP know about the new research? We turned to Janessa Broussard, RN, MSN, AGNP-C, to shed some light on the science behind this exciting new therapy, and offer a perspective on these new research findings.

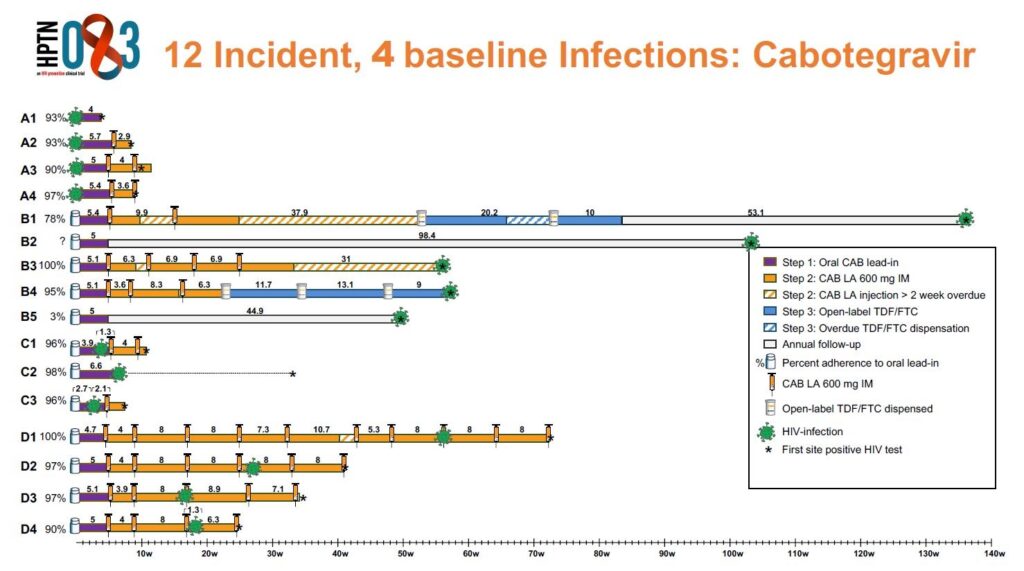

The HPTN 083 study included more than 4,500 men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men, who received either injectable cabotegravir or oral TDF/FTC (Truvada) for PrEP. Among people who were randomly assigned to receive cabotegravir, there were 15 HIV infections. Are these HIV infections a cause for concern?

Janessa Broussard, RN, MSN, AGNP-C: It’s worth a closer look at the HIV infections that happened during the study. Three were actually found to have happened before the study began, 5 happened in people with no recent exposure to cabotegravir (these people missed study visits, stopped receiving the injections, or never started them), and three people seroconverted during the oral “lead-in” phase (when they were taking oral cabotegravir, before beginning the injections).

So only 4 HIV infections seemed like true “failures”–or seroconversions that happened even when people were receiving cabotegravir injections on time. Unfortunately, in most PrEP studies there are some HIV infections. All 4 of these individuals achieved undetectable viral loads after starting an antiretroviral combination that did not include an integrase inhibitor.

Across the entire study, the HIV incidence was actually significantly lower in the cabotegravir group compared to the TDF/FTC (Truvada) group, with 12 infections in the cabotegravir group compared to 39 infections in the TDF/FTC group. 37 of the TDF/FTC infections occurred as a result of participants not taking enough doses to achieve suitable protection levels. So, the researchers could say that long-acting cabotegravir was “superior” to daily oral TDF/FTC. Overall, the long-acting cabotegravir injections were very, very effective in preventing HIV infections. The number of infections in the TDF/FTC arm that were attributed to suboptimal adherence provided further evidence that a long-acting option for PrEP is needed.

What are the reasons the HIV infections may have happened even when people were receiving on-time cabotegravir injections?

Broussard: We actually don’t know why the infections happened to people who received the cabotegravir injections, but researchers will continue to evaluate pharmacokinetic (PK) data to see what more we can learn about drug concentrations needed to offer full protection.

There is evidence that there is variability in the half life of the medication (how long the medication lasts in the body) depending on a person’s sex and BMI. It’s possible that these factors contributed to the seroconversions that happened in the HPTN 083 study.

Another possibility may be related to the injections themselves. The study medication was delivered in one 3 mL intramuscular injection into the gluteal (butt) muscle. 3 mL is a pretty large volume of liquid! So, there is a question in my mind about variations in injecting being a factor.

Some people who seroconverted when receiving long-acting cabotegravir for PrEP developed integrase inhibitor resistance mutations. Can you tell us a little more about what this is, and why it matters?

Broussard: Cabotegravir is an integrase inhibitor–a powerful, newer class of antiretroviral that is one of the preferred drug classes to treat HIV infection. “Resistance” mutations can develop when a person seroconverts while they’re taking an antiretroviral medication to prevent HIV, typically due to not having enough medication in their system. Basically, the virus mutates to evade the protection offered by a particular “class” or type of HIV medication. Integrase inhibitor drug resistance means that integrase inhibitor medications won’t work against the virus.

Two of the people in this study, who seroconverted while they had high enough levels of cabotegravir in their system, developed integrase inhibitor drug resistance. It’s not surprising that these people developed resistance, because detection of their HIV infection was delayed, and it took awhile for them to test positive, start HIV treatment, and get their viral loads fully suppressed.

There’s a lot of fear around resistance mutations, but thankfully we have multiple classes of antiretrovirals at this point. Because integrase inhibitors perform so well and are well tolerated, we [clinicians] favor them. But we still have safe and effective boosted protease inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), which were used successfully with individuals who seroconverted in this study.

Interestingly, out of the few people who seroconverted while levels of cabotegravir were falling in their body (during what is called the drug’s “tail”), none developed integrase inhibitor resistance.

Clinicians must remain aware of the potential for resistance. These medications have been well-studied. Nonetheless, it is not unusual for information to become known after the medication’s release. So there could be changes in how we approach some of these issues. At this point I see compelling evidence to use these medications in clinical practice.

As you plan to bring long-acting HIV treatment and prevention injections to the clinic, who are you thinking would benefit from these medications?

Broussard: It will be exciting to offer clients another option for HIV treatment or PrEP. This will be another strong option for people to consider. So I think we would make this available to anyone who chooses this option and believes it will be a good fit for their lives.

For instance, a long-acting injectable PrEP could be a good fit for a person who has a hard time remembering to take a pill every day, or just doesn’t want to have to take a pill every day. You just have to be able to come in consistently to the clinic to receive your injections–you don’t want to miss a dose or be late getting it.

Do you know when long-acting treatment for PrEP will be available?

Broussard: We’re hoping to have long-acting cabotegravir available for PrEP sometime this year (2021), but it has to be approved by the FDA first. We’re planning on creating an “express” injection clinic at our Market Street location (once we open again after COVID-19 risk lessens), which is a site that is convenient for the community.

We’re also excited about additional long-acting antiretrovirals that are being studied and plan to support further HIV prevention research. Lenacapavir, from Gilead Sciences, is a long-acting injectable medication that may only need to be taken twice per year for PrEP if it’s shown to be effective and safe. A medication named Islatravir is being studied as a once a month oral option and an implantable formulation.

Our PrEP & sexual health services are open!

Appointments are available at Magnet, the sexual health clinic at SFAF, for STI testing and treatment, PrEP services, trans health care, and more. Call 415-437-3450 to make an appointment. Appointments are free and insurance is not required.